December 05, 2023

We Need More Women on Bicycles

By Kasih Sabandar, Inclusive Urban Planning Associate ITDP Indonesia

The meaning of cycling varies greatly depending on cultural contexts and individual experiences, environmental surroundings, not to mention, it is constantly evolving. For instance, a child in the Netherlands might view a bike as a practical means to get to school, while during my upbringing in Indonesia, I considered my bike as a source of joy and spent my afternoons cycling around the neighborhood with friends. Both perspectives are equally valid and shaped by the unique environments we grew up in.

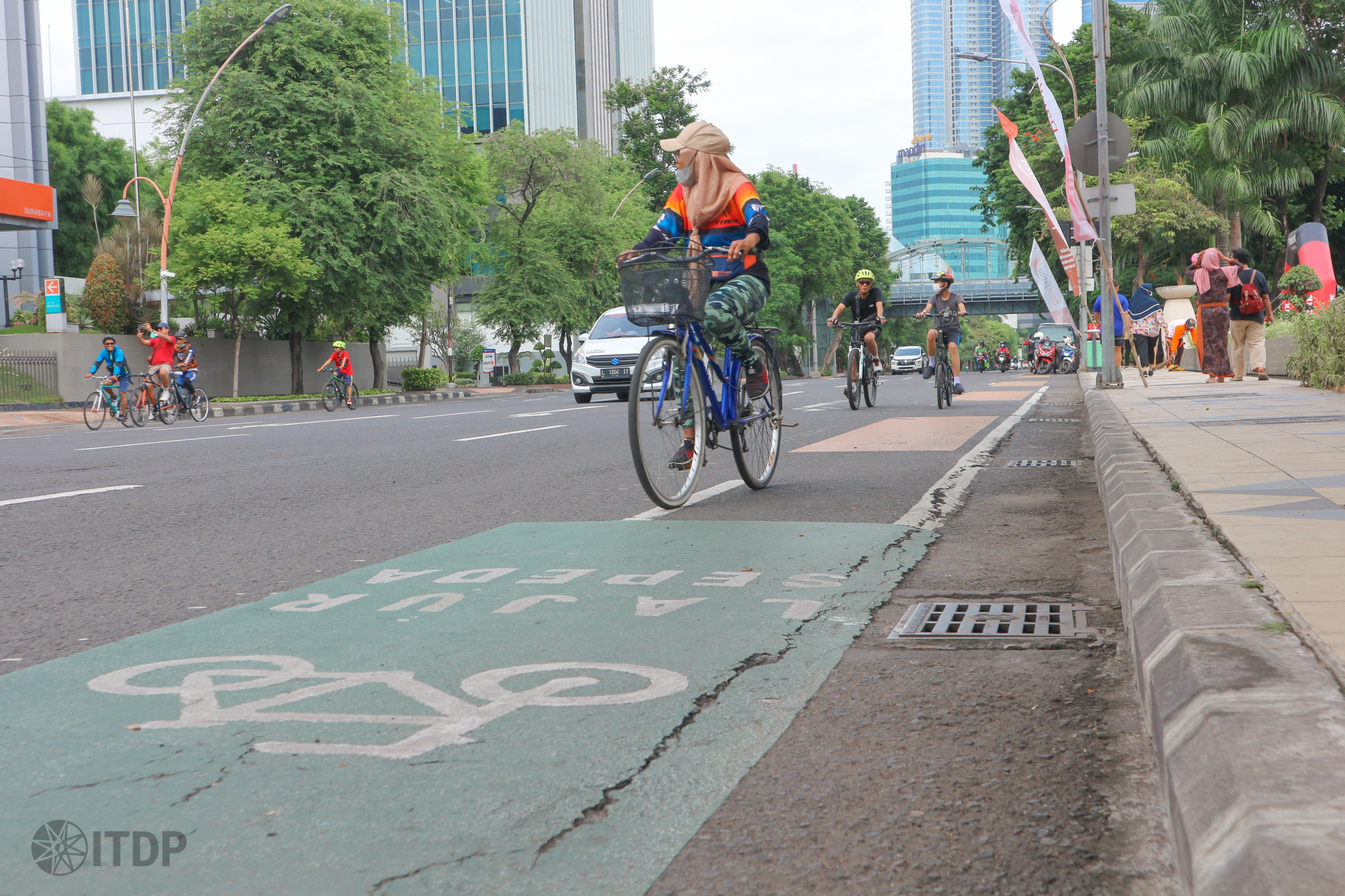

As time progresses, efforts have been made to improve the safety of cycling in Indonesia. For example, during the COVID-19 Pandemic, there was a huge increase in cyclists, leading to the development of cycling infrastructure in Jakarta, and other cities in Indonesia to support it as a mode of transportation. However, while the addition of cycling infrastructure was a positive step, it became apparent that it did not fully address the needs of women and other vulnerable groups. Surveys and input gathering revealed significantly lower participation from women compared to men, indicating an exclusionary trend. This can be seen in the considerable gap on the number of women participants compared to men on conducted multi-gender surveys such as in the Cycling Friendly Jakarta FGD in 2019 and the Perception of Cycling in the Sudirman Thamrin Street in 2021.

The lack of representation from vulnerable groups, especially women, in these surveys and planning processes can result in inadequate infrastructure that fails to meet their specific needs. This exclusion may also discourage women from cycling and limit their mobility and access to opportunities. To overcome these challenges, it is essential to prioritize gender equity, disability and social inclusion (GEDSI), throughout the planning, design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of cycling initiatives. By actively involving vulnerable groups, especially women, in the decision-making processes, we can create a more inclusive cycling community that breaks stereotypes and promotes access to resources and opportunities for all. The goal is not to replicate the Netherlands’ approach to cycling but rather to cultivate a safe and supportive environment for cycling that considers the unique needs and experiences of the Indonesian population.

Women Cycling Characteristics in Indonesia

Purpose of Cycling

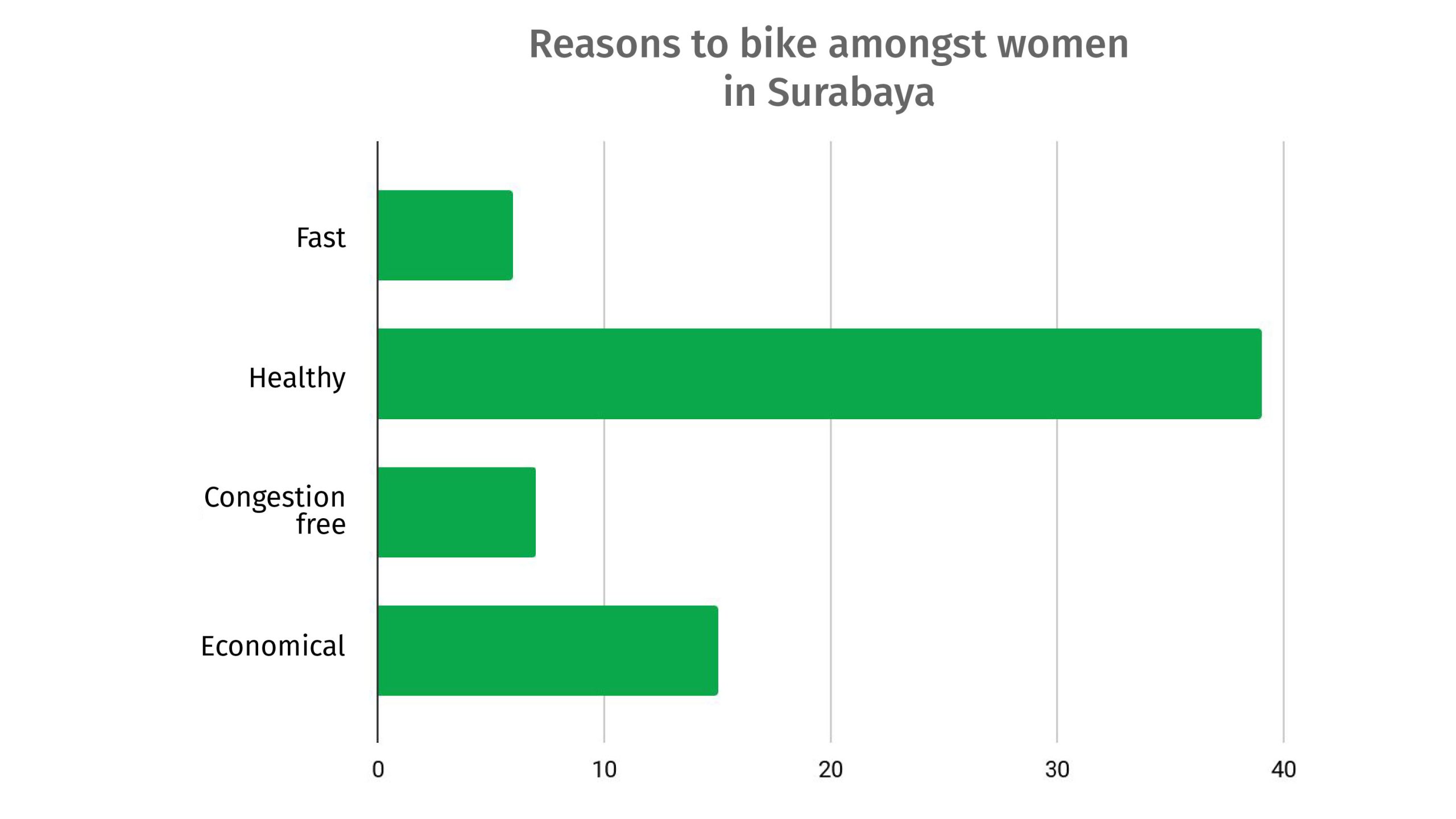

To understand the needs of women while cycling, it is first crucial to understand a woman’s cycling patterns. According to a survey conducted in Surabaya with 41 women participants (ITDP, 2022), health was proven to be the most outstanding factor that encouraged women to cycle. This factor was chosen by both commuting cyclists, beginner cyclists, and active sport cyclists. This may imply that cycling is still depicted as a way to keep women active, but some people choose to add more purpose to it, such as commuting. Furthermore, 37% of women respondents also claimed that cycling is economical, enabling them to save money for mobility needs. One respondent stated that the rise of the ride-hailing fee and the hassle of obtaining a driver’s license have actually influenced her to bike to work and exercise at least 2-3 times a month. These sentiments can also be related to the fact that women have less access towards private vehicles, therefore cycling can act as a relatively affordable solution to support a woman’s mobility.

Journey characteristics

In terms of distance, a 2022 survey in Jakarta on women cyclists revealed that 48% of the respondents’ journey consists of close range trips such as going to get groceries, or looking for snacks near the house. Close-range daily cycling trips generally account for trips no more than 5 km. This further emphasizes that women’s cycling behavior is much different from men, and cycling infrastructure that support women’s mobility should consider close range trips, or within the neighborhood scale, not just in large streets such as the Sudirman-Thamrin Street. On the other hand, long-range cycling trips are mostly done by courier and sport cyclists. It can range from 20 km to 70 km on weekends, sometimes done across multiple cities.

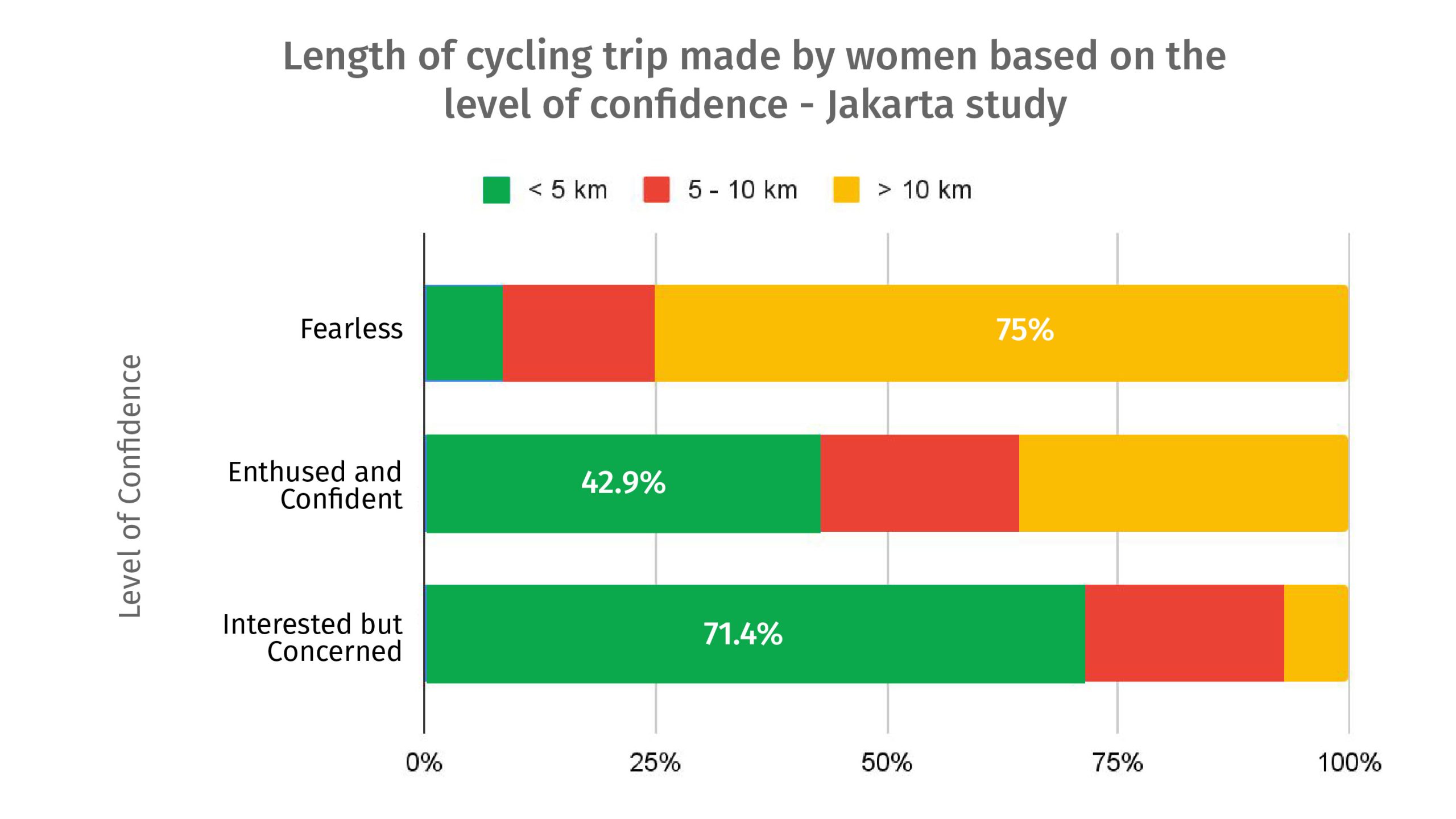

In choosing routes, women tend to choose routes depending on their level of confidence as well as their purpose of cycling. Women who cycle in main roads usually do so as they cycle for sport reasons, as the large roads allow for faster speeds. These women also tend to have a higher level of confidence whilst cycling, being comfortable cycling in mixed traffic roads with cars and motorbikes. On the other hand, local roads are usually used by women for close-range trips to local activities such as going to get groceries, to the ATM, or for recreational purposes. Nonetheless, most beginners would rather choose going through local roads rather than main roads because it is calmer and less busy so cycling is way safer, even though they admit that sometimes it takes familiarity to the local area to not get lost and can be uncomfortable due to speed bumps.

Type of bicycles

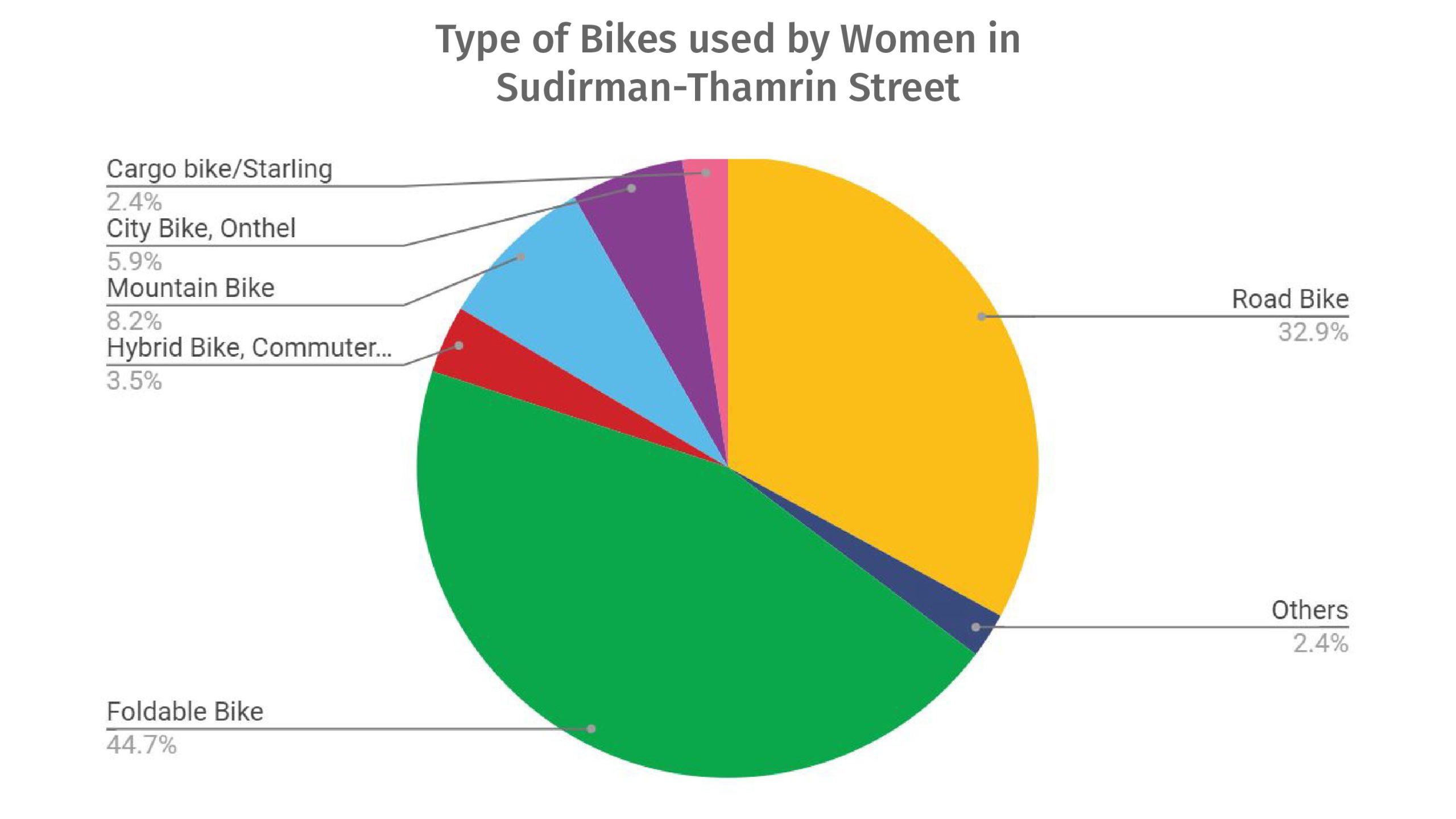

ITDP’s survey on the Sudirman-Thamrin street showed the different types of bikes used by women, in which folding bikes were the most dominant types of bike (37.5%). Folding bikes are the most common type of bikes for commuting as it is practical and flexible. Supporting bikes for first-last mile trips, folding bikes are also suitable for mix-commuters as they easily fit into public transportation fleets such as medium feeder buses or commuter trains. When bike parking is not available, women cyclists could take their folding bikes into the buildings they are visiting (e.g. office). They also come with a wide range of tire sizes; beginner cyclists could take advantage of the bigger tire diameter as it takes them to their destinations faster. On the other hand, non-folding bikes such as road bikes and mountain bikes are more popular amongst sport cyclists, including those who also bike for their day-to-day mobility.

Needs of Women Cyclists in Indonesia

Access to Bikes

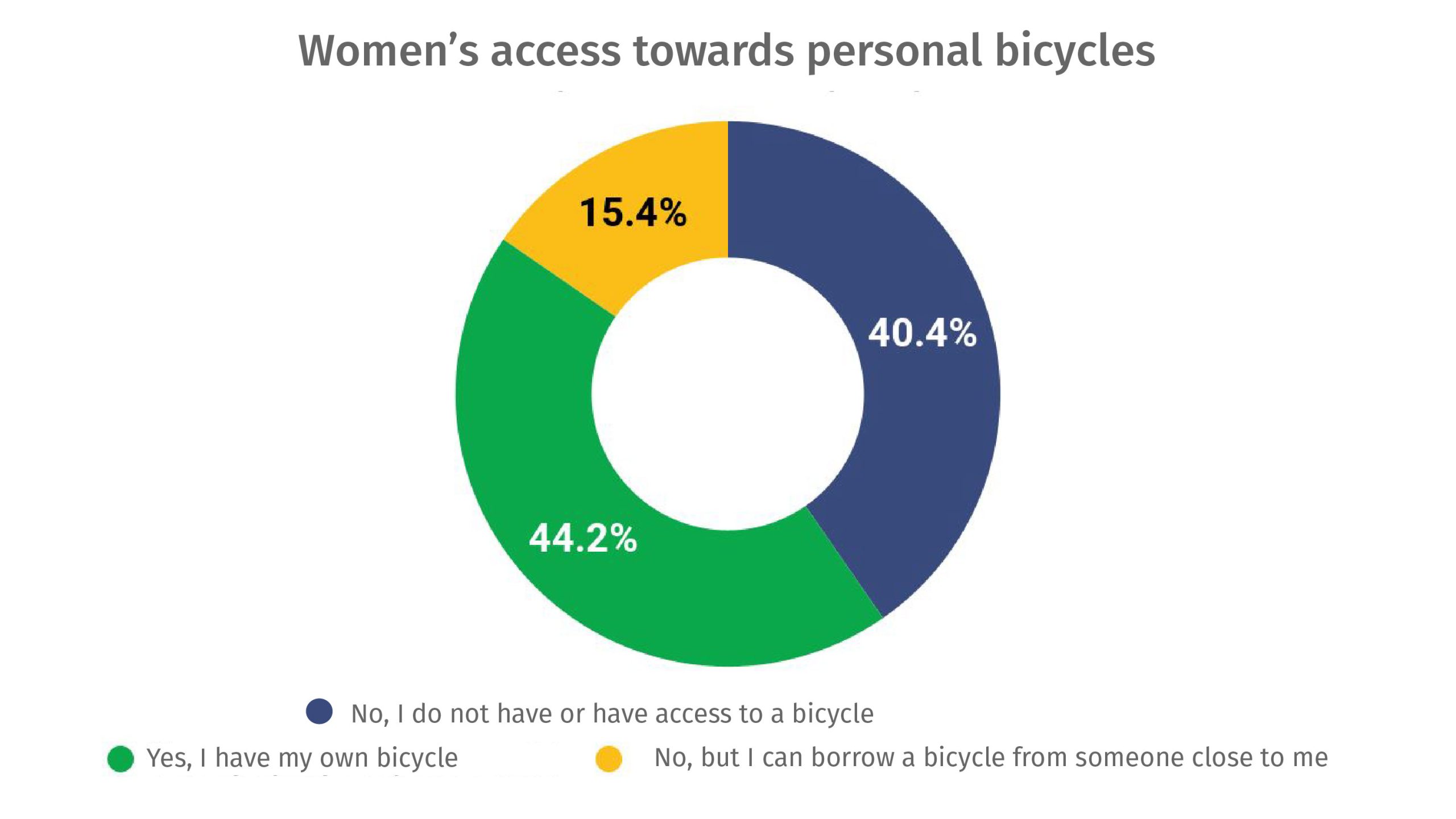

Women are less likely to have ownership of bikes which is shown in ITDP’s 2022 survey regarding the evaluation of bike sharing facilities. They are more likely to also borrow bikes from their close friends and/or relatives. This trend is similar to the fact that Indonesian women also have less access to private vehicles in general, such as cars and motorcycles, which is more prevalent in low income households in which traditional gender roles are still applicable. Here, the provision of bikesharing facilities can be a solution for those who wish to use bicycles as a means of transportation however do not have access to a bike.

Cycling Infrastructure

Women who have access to bikes may still not feel comfortable riding their bike due to the lack of proper cycling infrastructure to support their mobility needs. From ITDP’s 2021 survey regarding women and cycling, it was revealed that improvements in cycling infrastructure, such as the increase of protected bike lanes availability, parking facilities in public spaces, as well as safer cyclist crossings were the three aspects that were most important for women to ensure a bike-friendly environment. This was supported by ITDP’s 2021 survey in the Sudirman-Thamrin Street, which showed that women were more likely to use pop-up bike lanes than men, and deemed the speed of cars as well as lack of cyclist priority in points of conflict as the most dangerous situations for female cyclists. These surveys show that women are mainly concerned about their safety while cycling, mostly regarding having to interact with motorists during most of their rides, in which segregated biking lanes can be a solution to these concerns.

On top of safer roads to cycle on, the provision of cycling facilities to allow for mixed commuting can also support women’s mobility. As mentioned earlier, women who are less experienced in cycling are more likely to travel short distances. In this case, a full trip to work might be intimidating and Instead, allowing for cycling to be a first and last mile option may be a more realistic option. To support this type of mobility however, it is important for public transport operators to allow bikes on their fleets and have the proper supporting infrastructure within their stations and fleets for bikes.

Safety and Security

Common barriers cyclists have when wanting to shift to cycling for mobility is the fear of criminal activity such as getting mugged (begal) or getting sexual harassment/assault while cycling. One of the women cyclists who cycles for sport reasons shared her experiences getting robbed whilst cycling with two other cyclists in a suburban area in South Tangerang. These events may cause additional fear when having to cycle alone for one’s day-to-day mobility. The fear of being sexually harassed/assaulted was mentioned by many women cyclists, with one mentioning that she feels sexual harassment is more of a threat than being mugged. In reaction to the fear of being sexually harassed, cyclists have mentioned cycling with their partners to feel safer and to watch out for suspicious behavior from other road users, as well as stopping cycling forever due to the trauma experienced. Tackling this issue, an active bystander approach may help women who face sexual various stakeholders may increase public awareness regarding this issue, while also practicing the active bystander approach, Improve reporting mechanisms, and enhance safety facilities such as CCTV, lighting, and the addition of panic buttons.

![[ENG] Infographic Staff Notes - GEDSI in Cycling (5)](https://itdp-indonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/ENG-Infographic-Staff-Notes-GEDSI-in-Cycling-5-scaled.jpg)

What’s Next?

In Indonesia, women have become an important part of the cycling community, embracing biking for various reasons such as getting around economically or enjoying outdoor adventures. However, to make cycling more inclusive, we need to consider the specific needs of women cyclists. Safety and accessibility are key, so we should invest in better bike paths and involve women in planning. Understanding women’s unique mobility patterns and applying them to support short distance travel and mixed modes is also crucial if we want to see more women cycling. Lastly, ensuring security of women by actively practicing and campaigning for active bystanders and ensuring security facilities will allow more women to cycle independently and freely.