January 22, 2024

Comprehensive Planning is a Game-Changer for Walking and Cycling in Jakarta

By Mega Primatama, Urban Planning Associate II ITDP Indonesia

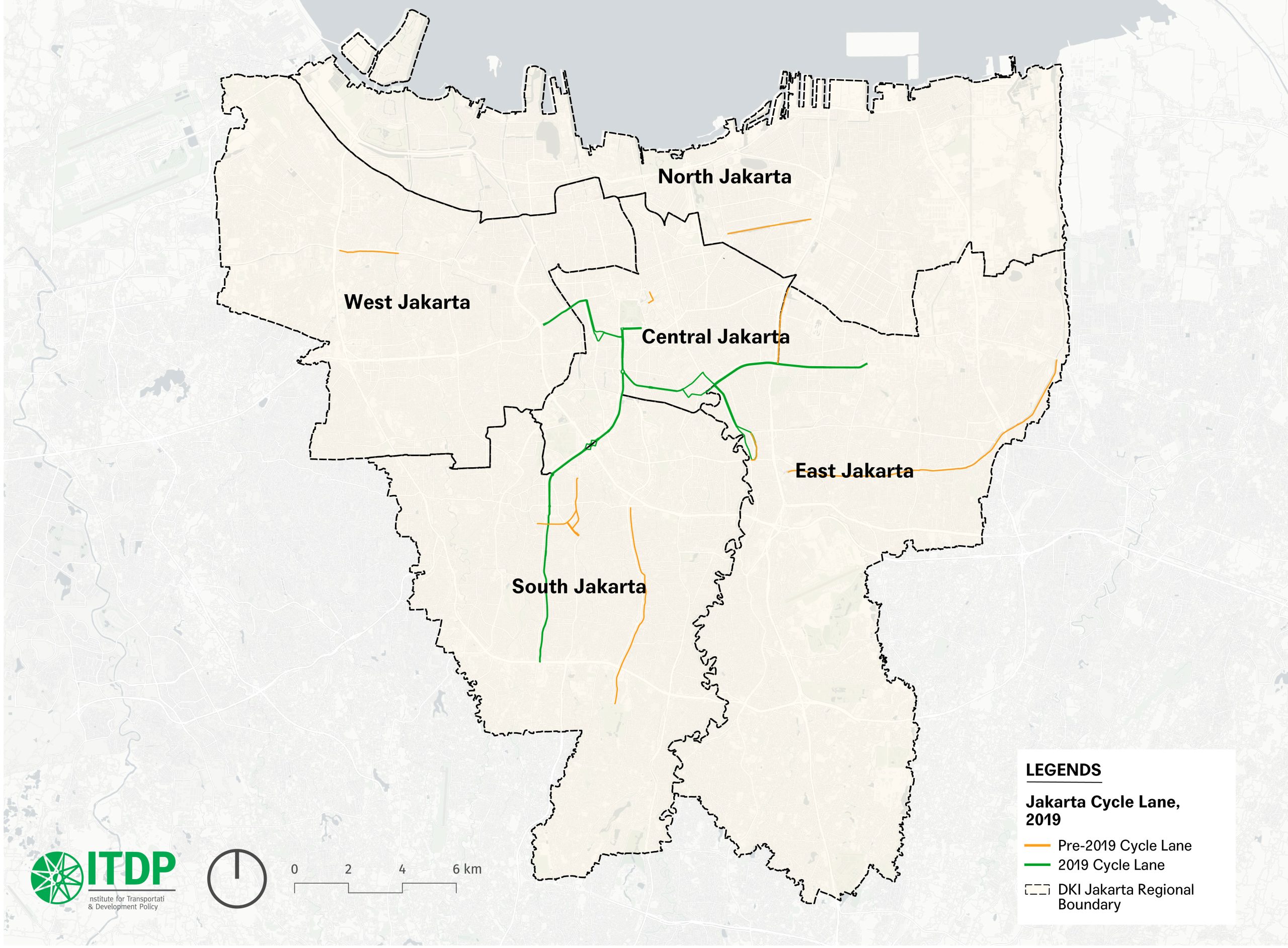

On 20 September 2019, we witnessed the inauguration of Jakarta’s new active mobility infrastructure’s cycle lane network. What differentiates this infrastructure is that this cycle lane went through a public participation process, resulting in a cycle lane network consisting of 63 km of cohesive and continuous cycle lane, spreading from Central Jakarta to the west, east, and south parts of the city. The development of this 63 km cycle lane would then lead to creating a roadmap, aiming for 500 km of cycle lane in Jakarta built by 2030.1

Two months later, parts of this newly-built cycle lane were suddenly demolished for the sidewalk widening projects for Cikini Raya and Diponegoro Street, despite the regulation stating that a road mark shall not be erased for at least two years since its creation. Despite the criticism and claims from the government that the cycle lane will be reinstated2, this new sidewalk development raises a significant issue: inadequate coordination between the in-charge stakeholders in Jakarta street space.

Why Comprehensive Planning Matters?

With more people commuting due to high jobs availability in the centre of urban areas, to move more people, support the urban context, and ensure a high-quality public realm, urban streets must be equitably distributed to the needs of its many users by transforming into multi-modal streets with the prioritization of walking, cycling, and public transportation3. ITDP Indonesia also recognizes the importance of walking and cycling infrastructure as it creates first and last-mile access to cover the first and last journeys using public transportation4. Therefore, this first and last-mile gap must be adequately addressed to ensure optimal public transportation usage and coverage.

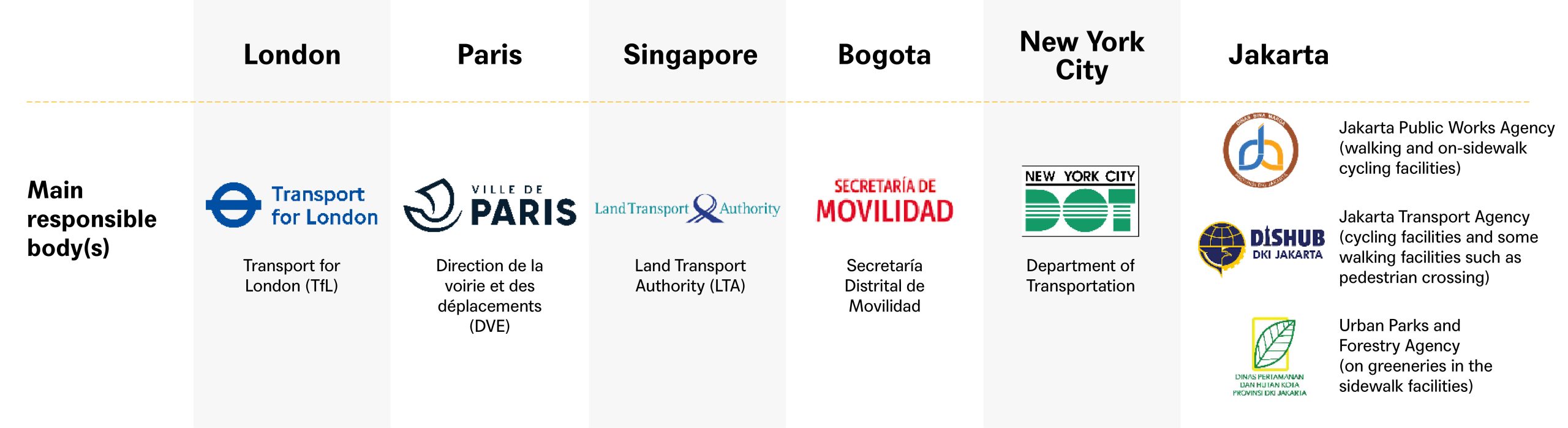

The urban streets’ significance in supporting the city’s mobility requires proper communication of many stakeholders and must be well-coordinated. In a few practices in cities across the globe, most of the planning for the walking and cycling infrastructure is usually coordinated under one transportation board. However, in the case of Jakarta and Indonesia, the task is split. ITDP Indonesia identifies on-site implementation as divided into two central engineering agencies: Jakarta Transport Agency and Jakarta Public Works Agency5. Jakarta Public Works Agency works on the road and sidewalk construction, including the on-sidewalk cycle lane and sidewalk furniture such as bench, lighting, and wayfinding.

On the other hand, the Jakarta Transport Agency took charge of tasks such as traffic engineering and road marking, including crossing and on-road cycle lanes. However, other agencies are also in charge of the pedestrian facilities, such as the Urban Parks and Forestry Agency, which oversees greeneries in the sidewalk facility. Compared to other global cities, the task delegation is apparent in the table below.

| City | Main responsible body(s) |

|---|---|

| London | Transport for London (TfL) |

| Paris | Direction de la voirie et des déplacements (DVE) |

| Singapore | Land Transport Authority (LTA) |

| Bogota | Secretaría Distrital de Movilidad |

| New York City | Department of Transportation |

| Jakarta | Jakarta Public Works Agency (walking and on-sidewalk cycling facilities) and Jakarta Transport Agency (cycling facilities and some walking facilities such as pedestrian crossing)

Additional agencies: Parks and Forestry Agency (on greeneries in the sidewalk facilities) |

In 2022, Jakarta built 214.64 km of sidewalk and 301.71 km of cycle lane6. To avoid the same “mishaps” such as disconnected networks and wasted resources that happened in Cikini Raya Street and Diponegoro Street, the government must embark on creating a single plan for developing the walking and cycling network across Jakarta, and a leading agency will lead that to coordinate the city-wide walking and cycling mobility plan. The government must also collaborate with as many related stakeholders as possible to synchronize the walking and cycling plan with all existing plans towards a more integrated approach.

Acknowledging the Problems and Start Planning

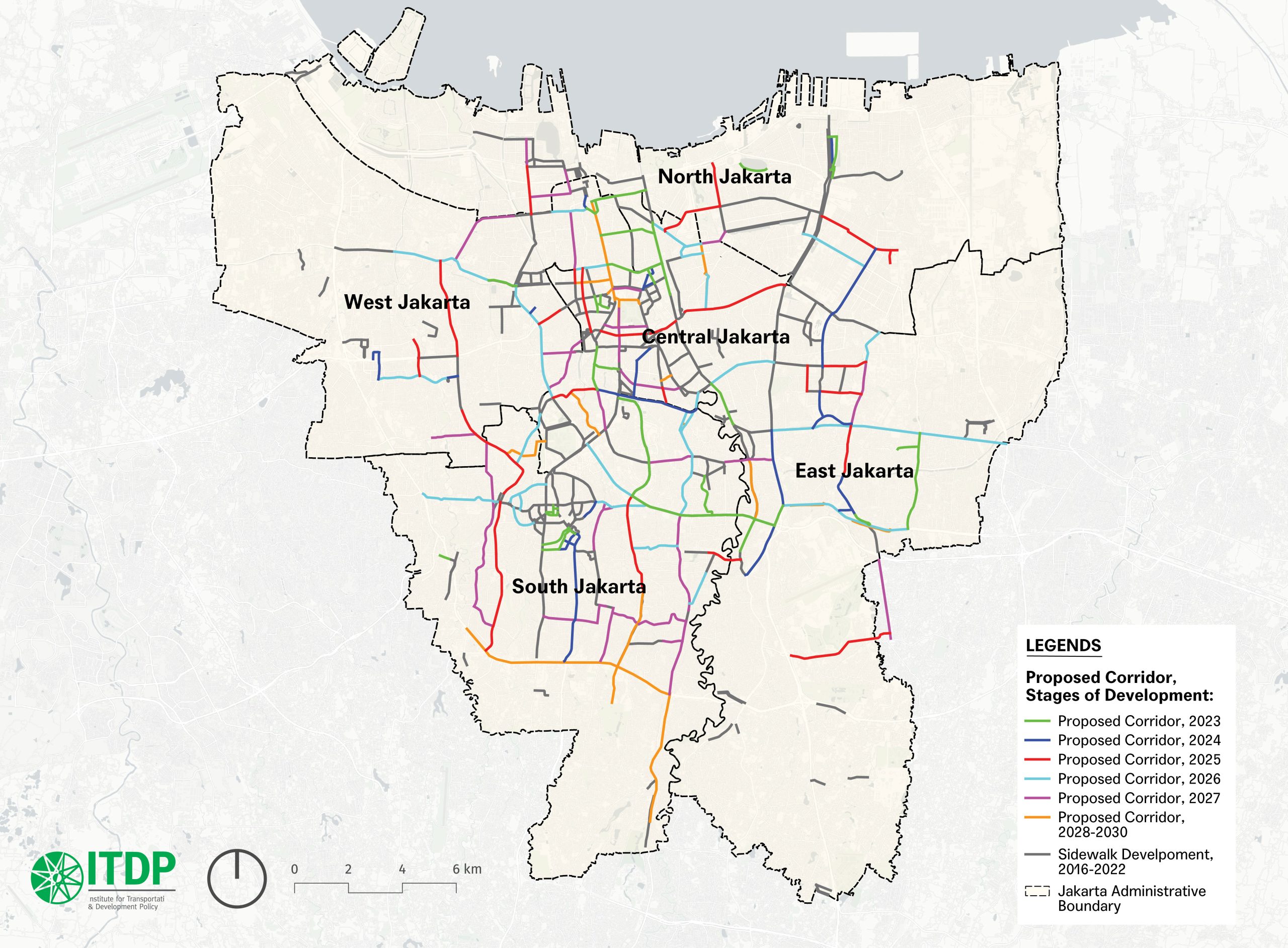

The approach on which street must be improved, and in what year, should be based on integrating the scattered transport-based city-wide strategic plans and prioritizing street intervention based on strings of criteria such as land use plans, public transportation availability, road hierarchy, and public facilities. Besides the technical method, the approach of creating integrated planning is also to recognize that many stakeholders are involved in the urban street space, so the government must coordinate with those stakeholders, discuss their plans and timeline to accommodate other stakeholders’ plans, and fit it into the final plan.

Besides determining the locations and construction timeline, the government should also consider the urban street space to prioritize walking and cycling activities, which has to follow the latest regulations on walking and cycling infrastructure with inclusivity aspects in mind. To create a street prioritization list for upgrading, a set of criteria and indicators could be formulated through the available municipal data to identify and analyze the importance of a certain street. The data that could benefit this purpose include regional policies prioritization, sidewalk condition, mass transit hub availability, and forecasted demand, cycle lane network plan, road classification, public facilities available, and frequency of public dissatisfaction reports. After creating the sets of indicators, a scoring system could be added to rank the prioritized streets.

After the list is completed, the next task is to fit these prioritized streets into all infrastructure planning in the city, such as the development of the metro or even fitting it with the existing street upgrading projects. This mix-and-match step should also fit within the budget availability, its ability to form a grid of continuous networks, and, if any, the annual target of the city’s sidewalk and cycle lane development.

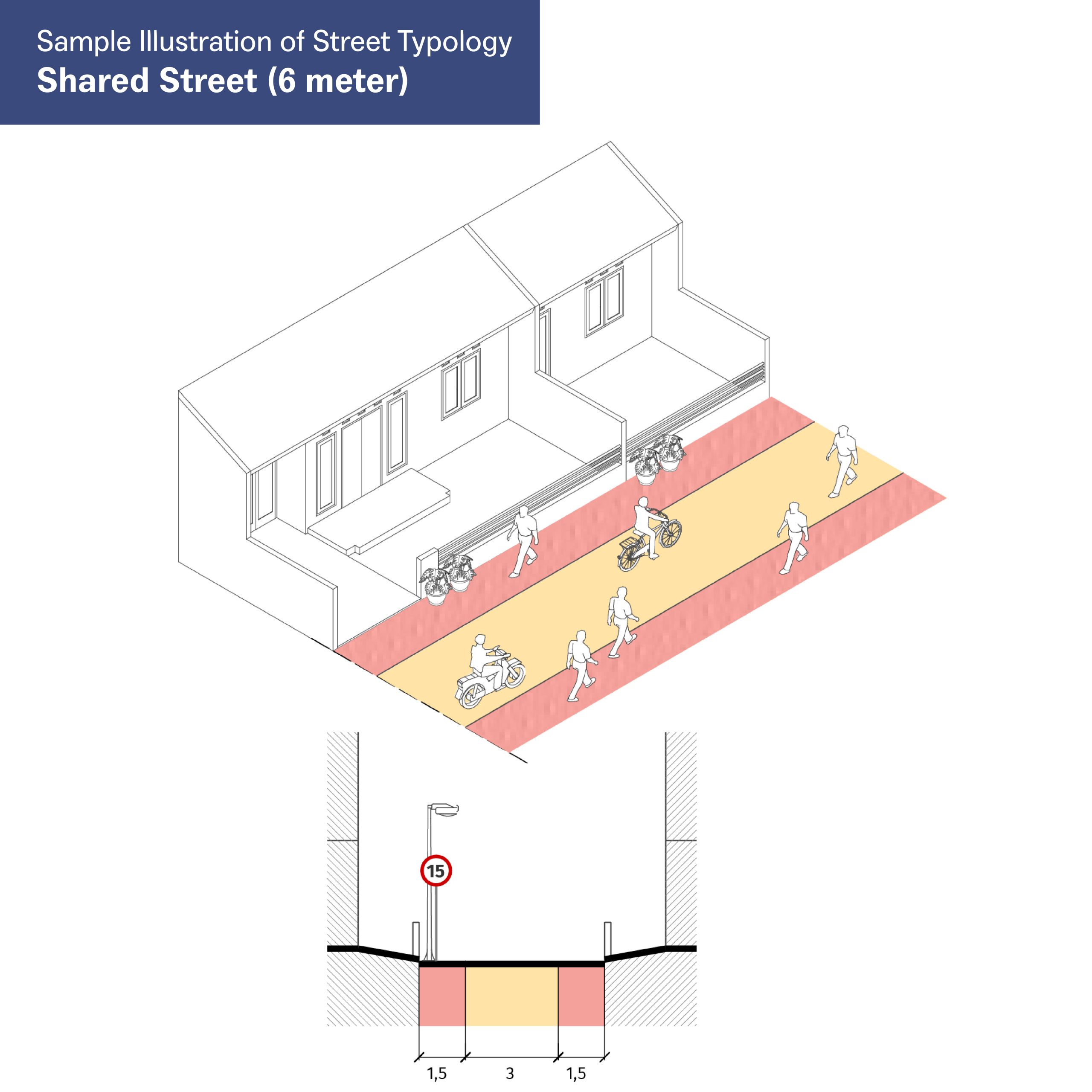

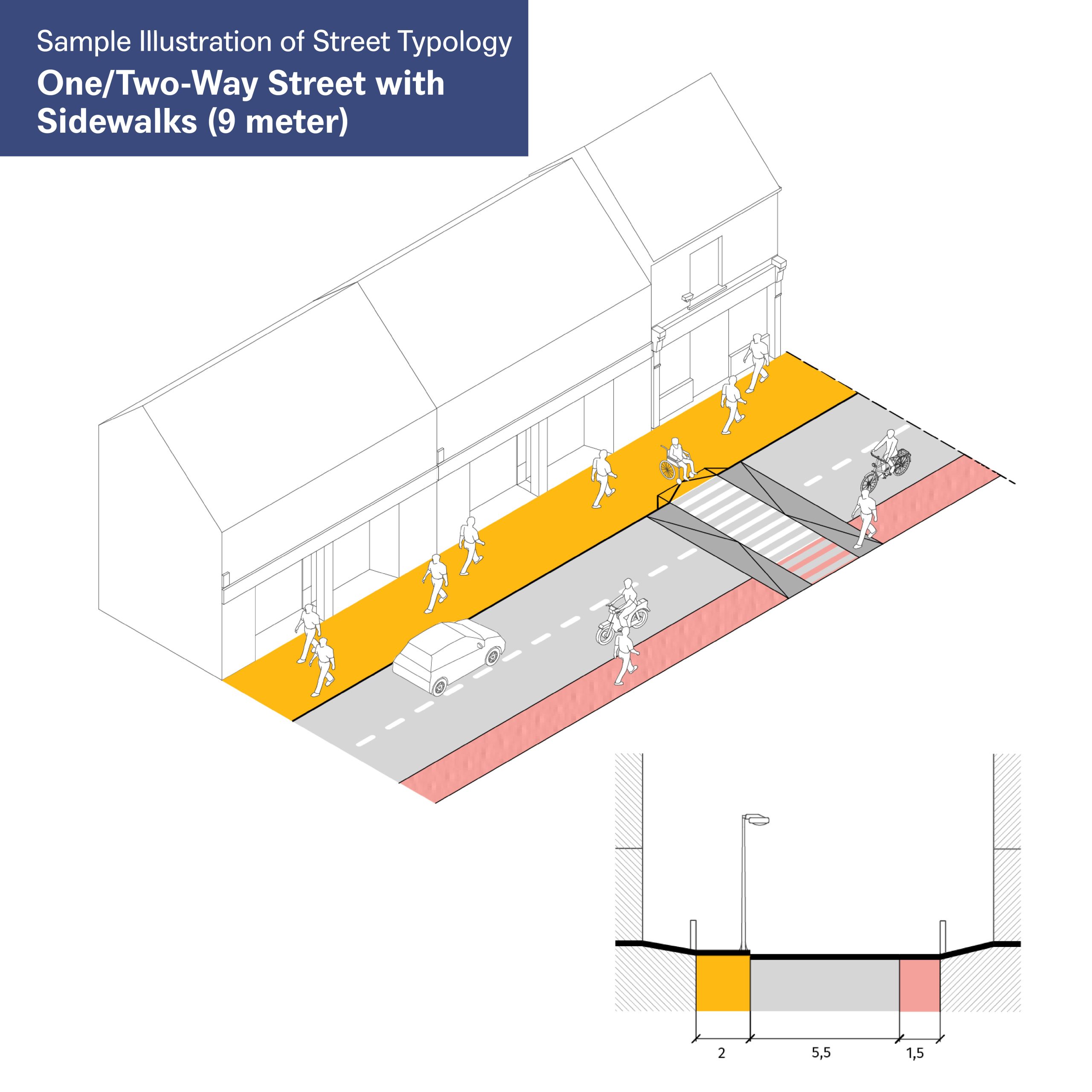

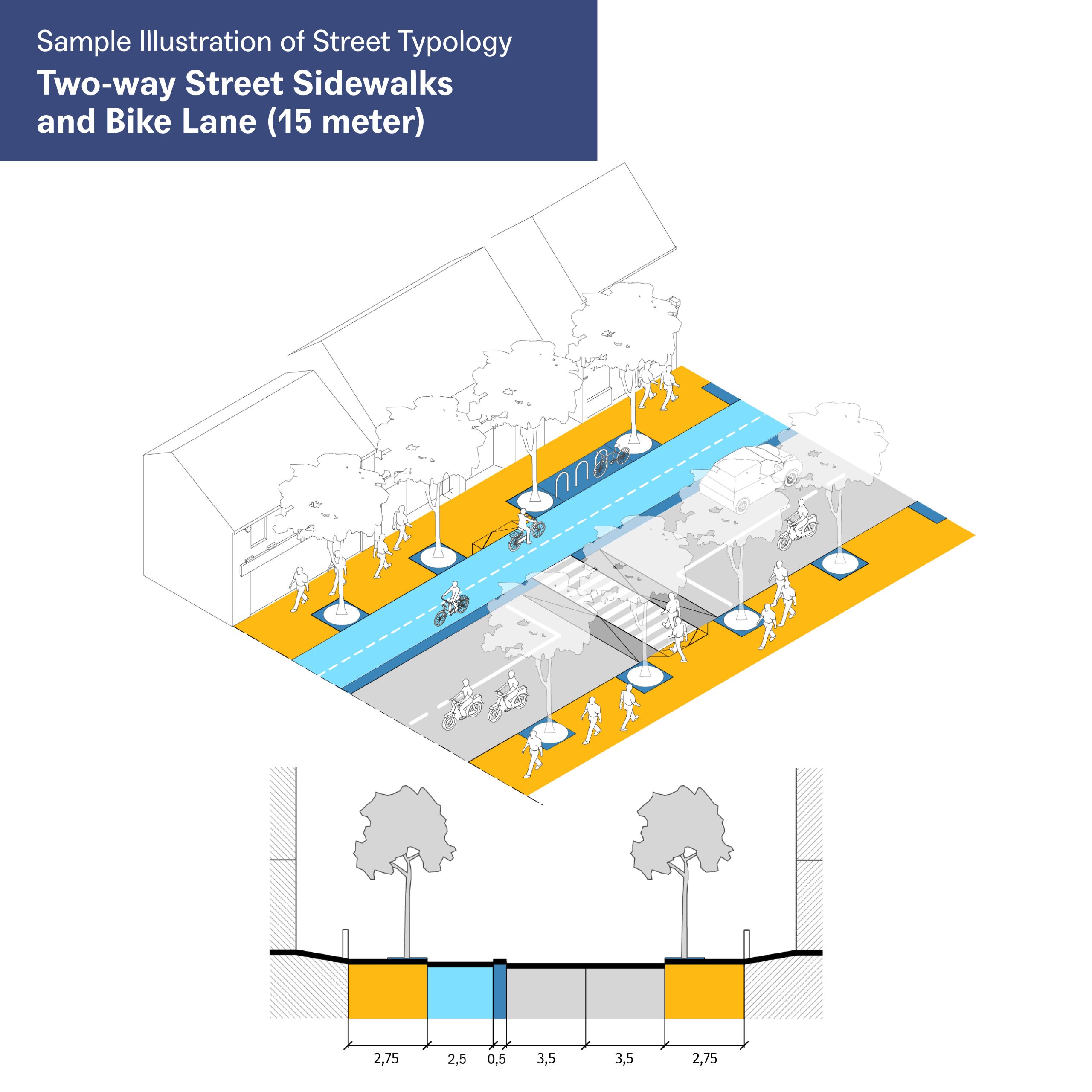

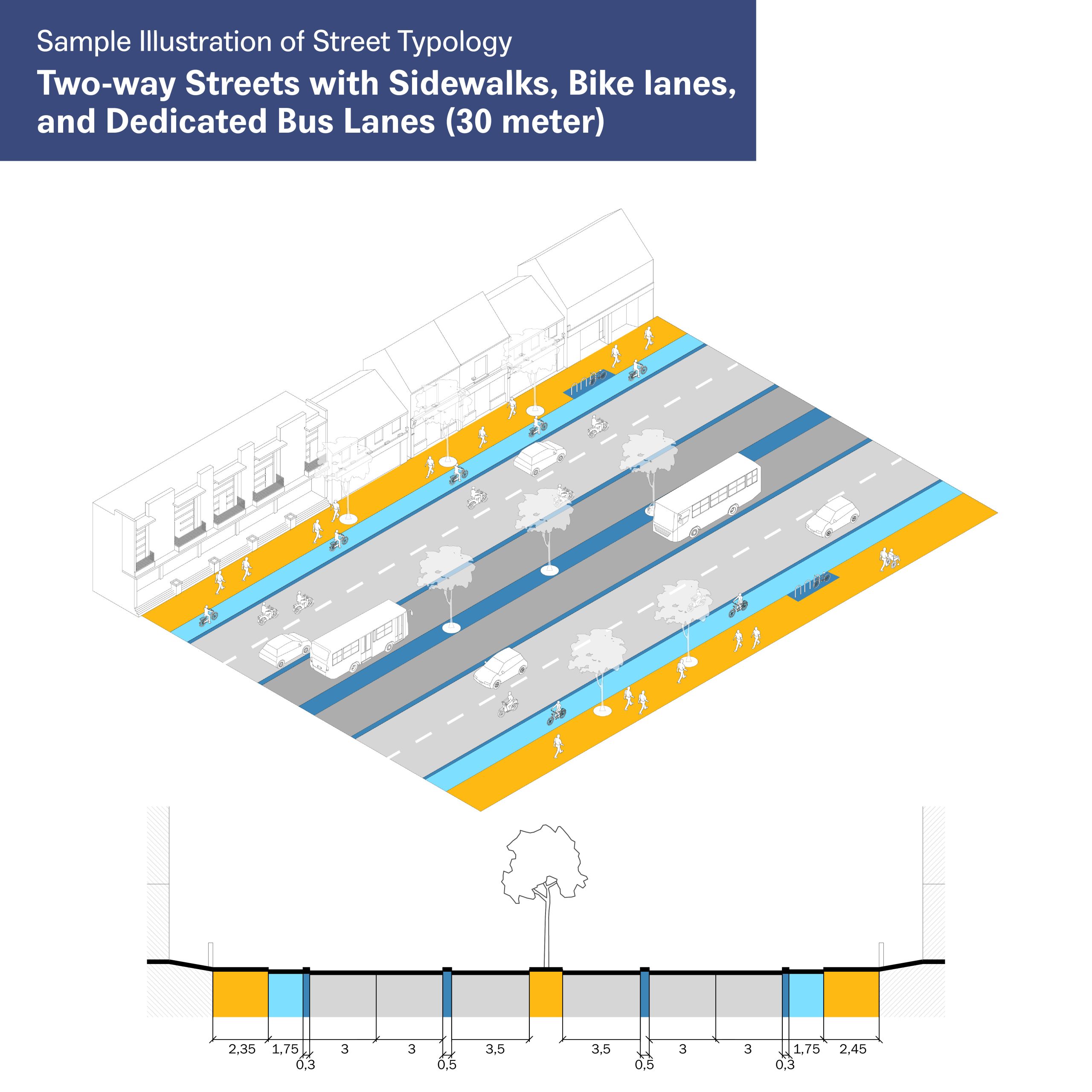

Along with the recommendations, there are 28 typologies. The typologies are based on the existing width, land use, cycling network plan, and public transport service on the streets. These are the recommended typologies for 15-meter and 30-meter widths of roads with mainly commercial land use.

What to Expect?

The planning process for an urban street must be comprehensive. In the first step, the relevant stakeholders must recognize each agency’s role in creating an efficient urban mobility system that prioritizes walking, bicycling, and public transportation. Afterward, they must coordinate their intentions on the urban street plans and sort the development priorities and stages to see which agencies could perform the first stage or collaborate in certain project stages.

Through this report, which intends to merge Jakarta’s walking and cycling infrastructure plan, the government is expected to start interagency coordination to connect the plans and fill the gaps that may be found. A well-connected walking and cycling facility in the city, built with sustainability and inclusivity, could expect various benefits, such as a less polluted environment, health improvement, sustainable economic development, and affordable mobility. Other positive impacts include increased safety, reduced private motorized vehicle dependencies, economic activity boost, and improved life quality.

With the street already improved to ensure all sustainable transportation gets the priorities, densification of the surrounding transit hub and corridor could be conducted hand-in-hand with this road improvement to optimize public transport services and create a vibrant and resilient neighborhood.

1Anies Optimistis Jalur Sepeda di Jakarta Capai 500 Kilometer. Republika (June, 2022)

2Baru Diuji Coba, Jalur Sepeda Cikini Dibongkar Demi Trotoar. CNN Indonesia (November, 2019)

3GDCI, 2016. Global Street Design Guide. Island Press

4ITDP Indonesia, 2022. Mobilitas Inklusif Kota Medan

5ITDP Indonesia, 2020. Visi Nasional Transportasi Tidak Bermotor.

6Data by Jakarta Public Works Agency and Jakarta Transport Agency, 2022

7Abdelaal, Mohammad (2015). Green Mobility as an Approach for Sustainable Urban Planning. IJIRSET, 4(8), 6949-6958

Read the full document titled “Peta Jalan Pengembangan Infrastruktur Pejalan Kaki dan Pesepeda DKI Jakarta 2023 – 2027.”