July 03, 2025

How Are Electric Buses Progressing Under Indonesia’s National Electrification Commitment?

By Rifqi Khoirul Anam, Transport Associate ITDP Indonesia

Six years have passed since the Indonesian Government established a national commitment to promote Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) through Presidential Regulation (Perpres) No. 55/2019, later updated by Perpres No. 79/2023. Since then, electric buses for public transport have gradually been adopted by cities across Indonesia. Starting with Jakarta in 20221, other cities like Medan, Surabaya, and Pekanbaru have followed suit. Over this period, ITDP Indonesia has witnessed how cities have navigated technical, regulatory, and financial challenges. While progress has been made, the road toward large-scale, efficient, and sustainable bus electrification remains long and steep.

Electric Bus Initiatives Across Indonesian Cities

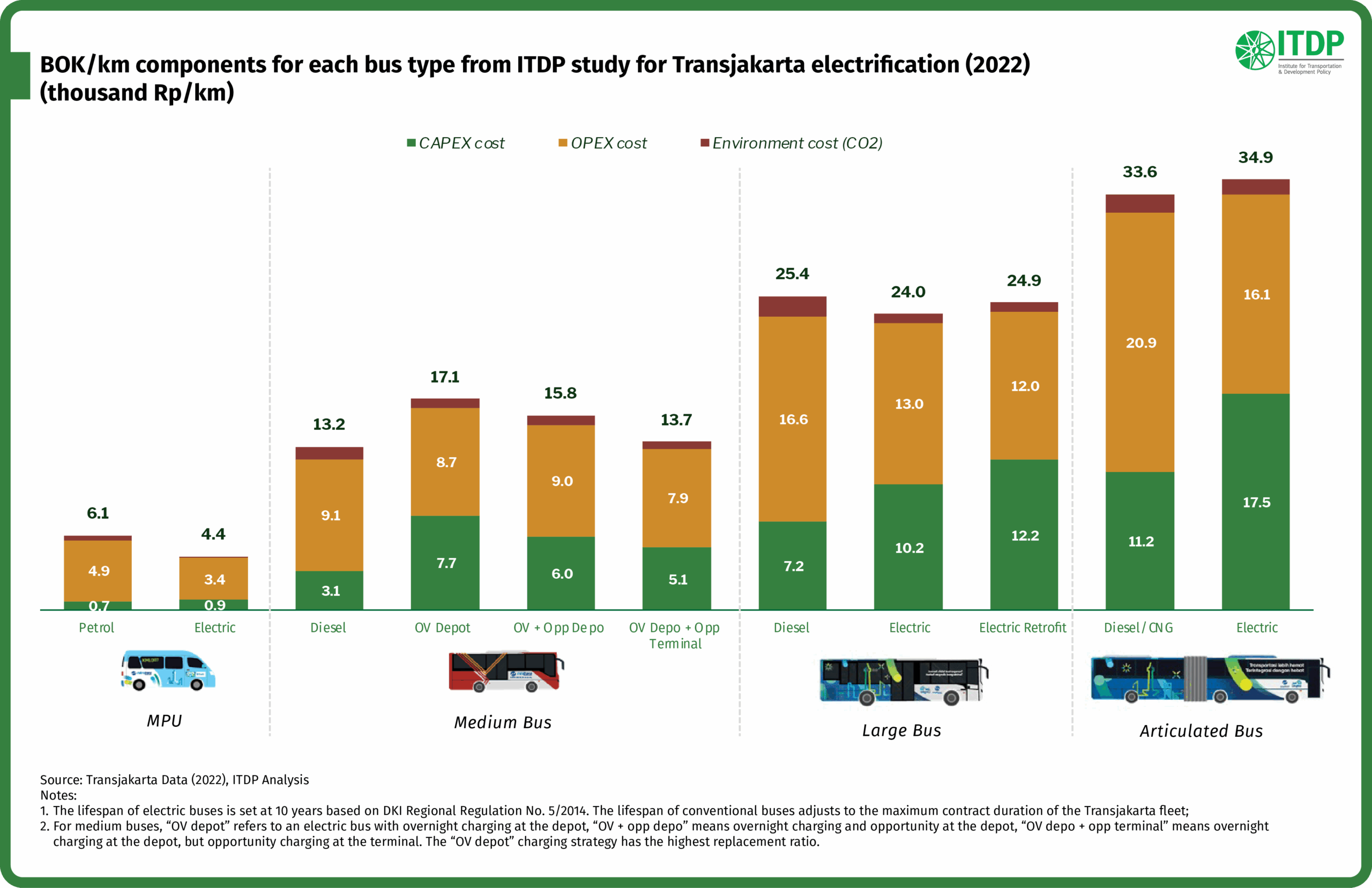

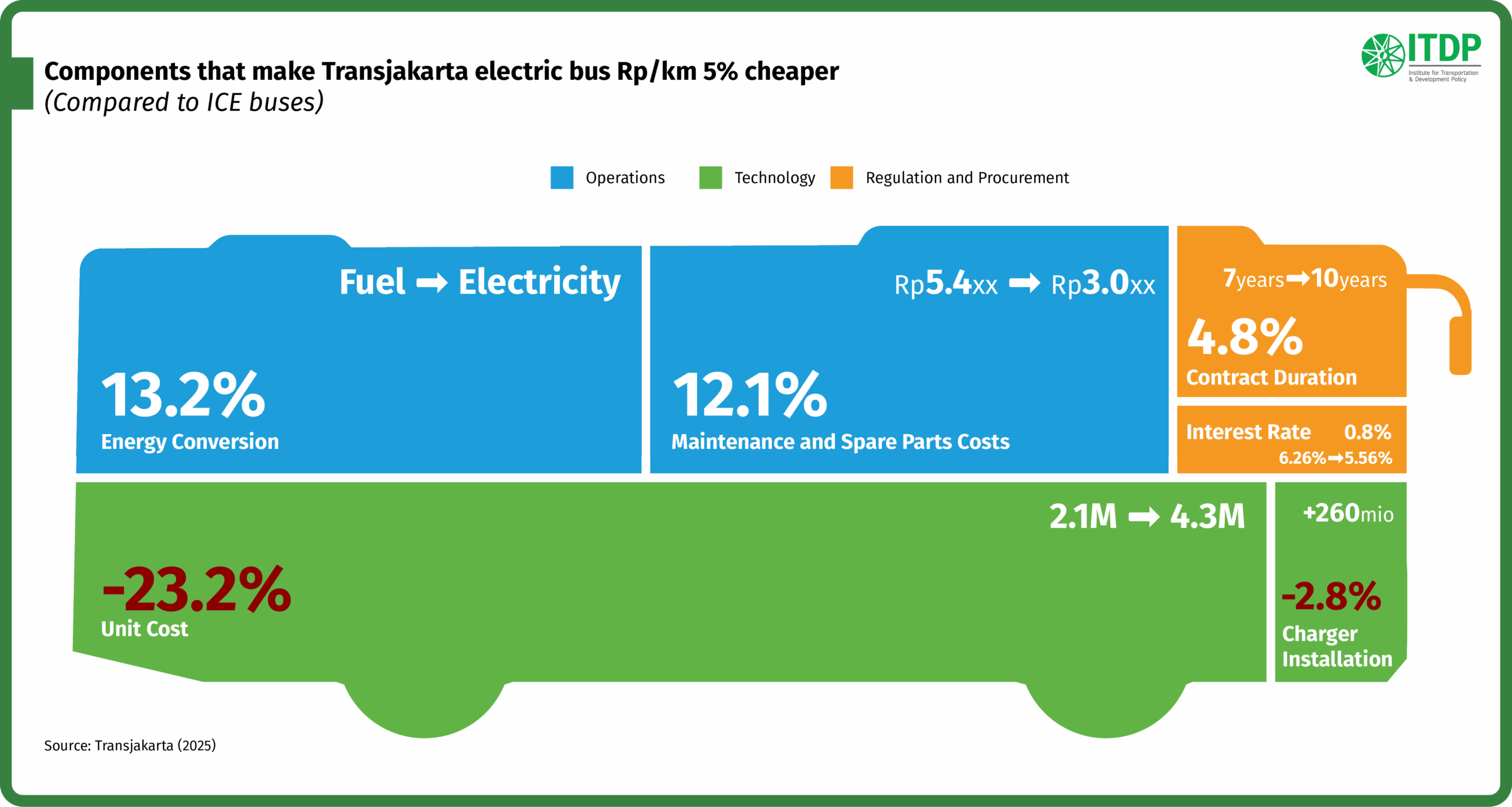

Each city in Indonesia has its characteristics. Jakarta, with its strong fiscal capacity and an established public transport authority in the form of a regional-owned enterprise (BUMD), has been able to move faster in implementing bus electrification. The electrification of Transjakarta buses began in 2019, when limited trials were conducted for several electric bus models. In 2022, ITDP Indonesia began assisting Transjakarta in monitoring and evaluating electric buses to ensure that performance and lessons learned in early electric bus operations were well-documented. In the same year, with ITDP’s assistance, the Jakarta Provincial Government set an ambitious target of 100% electrification of public transportation to be achieved by 2030, as outlined in Governor Regulation No. 1053/2022. By 2024, the vehicle operating cost per kilometre (BOK/km) for Transjakarta’s electric buses was already 5% lower than that of conventional buses, in line with ITDP’s 2022 study projections. With the same amount of subsidy, the Jakarta Provincial Government could potentially operate more buses and reach more residents.

Besides Jakarta, Medan and Surabaya also operate a significant number of electric buses. Since 2024, Medan City has implemented 60 units of electric buses as part of the TransMebidang BRT. In the same year, Surabaya City deployed 12 electric buses, following a previous operation of 14 electric buses for the G20 Summit. Cities like Yogyakarta and Semarang have begun operating two units of electric buses each.

Although there have been aggressive efforts to transition to electric buses, most notably through Transjakarta’s large-scale rollout and similar initiatives in a few other cities, most cities across Indonesia still struggle with implementation. Fiscal constraints, institutional instability among public transport authorities and operators, and inconsistent national-level targets continue to hinder the wider adoption of electric buses, leaving many regions unable to experience the electrification benefits that Jakarta has already begun to enjoy.

Lessons from Three Cities

The lessons learned from electric bus implementation in Indonesia have become increasingly diverse, as highlighted in ITDP’s recent study, “Reform Strategy and Roadmap for Public Transport Electrification”, conducted in three cities: Surabaya, Surakarta, and Pekanbaru. The study emphasises that bus electrification is not merely about adopting new technology; it is also a tool for reforming urban public transport services, including:

- Gradual fleet expansion to improve route coverage and service quality by meeting headway standards as outlined in the Minimum Service Standards (SPM);

- The need to explore contract models that reduce fiscal burdens on local governments while maintaining, or even improving, service quality, tailored to each city’s specific characteristics; and

- The importance of inclusive infrastructure strategies that enhance accessibility for users and help maximise the impact of electrification.

Taking city-specific contexts into account, ITDP Indonesia also recommends that bus electrification roadmaps could begin with public minibus services (feeder services) due to their lower cost requirements and potential to expand public transport coverage. Reflecting this recommendation, Pekanbaru officially launched its electric feeder service in June 2025, making it the first city in Indonesia to operate electric feeder buses beyond a trial phase.

The study further found that combining electric bus adoption with contract model adjustments could potentially reduce per-bus subsidy needs by up to 29% for feeder services in Surakarta, similar to findings from ITDP’s 2022 study on Transjakarta’s electrification. This shows that increasing bus fleets to improve public transport service quality is feasible for other cities across Indonesia. Although the upfront investment for electric buses remains significantly higher, the reduced operational and maintenance costs of electric buses are much cheaper than conventional diesel, gasoline or gas-fueled buses.

Challenges of Scaling Up Nationally

In 2019, ITDP Indonesia developed and published a guide to public transportation institutional reform that served as the basis for the “Electric Bus Planning Guideline for Urban Public Transportation”. Over the past five years, ITDP has developed studies and provided support to eight cities, including the national government, in their transition to electric buses, as embodied in the “Electric Bus Planning Guidelines for Urban Public Transportation”. From this study, we learned that:

- Each city faces unique challenges, requiring tailored and city-specific approaches.

- Without binding national targets, sufficient incentives, and clear guidelines, scaling up electric bus adoption will be difficult to achieve.

The studies also show that cities need guidance to electrify their public transport. Not only guidance on technology selection, such as electric bus specifications or charging strategy guidance, but also on assessing city readiness, choosing appropriate contract models, and developing business models to ensure electric buses move beyond the trial phase.

In the past six years, the variety of electric bus models available to Indonesian cities has grown significantly. Until 2020, there were fewer than five models being tested. Since 2022, a number of local body shops have begun producing CKD2 electric buses in collaboration with global manufacturers. By 2024, Transjakarta will have operated electric buses with TKDN3 above 40% and tested more than 20 models, including large and medium buses. Surabaya has also started operating medium-sized electric buses regularly. Despite the growing variety of available models, most deployments remain at small-scale trial stages. Mass production has yet to take off, primarily due to a lack of demand certainty, especially from the public transportation sector, which continues to make private sector players hesitant to take further steps.

Furthermore, public transport electrification cannot focus solely on government-operated services. Municipal transport and other semi-formal services—often run by cooperatives or individuals—remain the backbone of urban mobility in many cities. Without including this segment, achieving significant emissions reductions from the transport sector will be difficult.

Among the many challenges faced by both cities and the private sector, one element stands out as most critical: a strong, legally binding national commitment.

The national government has included bus electrification in several strategic documents, such as the National General Energy Plan (RUEN), which sets a target of 10% of urban public transport using electric buses by 2025. The Ministry of Transportation has also set targets of 90% electrification for mass urban public transport by 2030, 100% by 2040, and full electrification of public minibus services—typically used for feeder services—by 2045. However, on-the-ground realities show that these targets are almost impossible to achieve due to the lack of a clear regulatory framework. As of today, only 376 electric buses are operating in five cities across Indonesia.

Furthermore, as of today, electric buses for urban public transport are still not explicitly included in the national emission mitigation strategies for the transport subsector, including the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). In fact, the study “National Roadmap for Urban Public Transport Electrification” conducted by ITDP and supported by ViriyaENB shows that 100% electrification of public transportation in 11 cities can reduce GHG emissions to 24% by 2030, equivalent to approximately 900.000 ton CO₂ or the same as planting 3.6 million trees that grow for 10 years.

The role of the national government is vital, from setting clear and consistent targets to providing fiscal and non-fiscal incentives for operators, manufacturers, and local governments so that electric buses can become a widely adopted and replicable net-zero emission mobility solution. Without it, electric bus programs risk becoming expensive, unsustainable FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) initiatives, especially when most passengers prioritize reliable, high-quality public transport services, regardless of the vehicle technology being used.

1 While Transjakarta began limited trials of electric bus models in 2019, regular operations commenced in 2022.

2 CKD (Completely Knocked Down) is a production method in which vehicles are shipped in separate components to be assembled domestically. This scheme is commonly used to increase local content and reduce import costs.

3 TKDN (Domestic Component Level) is the percentage value of the production components of goods and services that come from within the country. TKDN is used as an indicator of the level of production localization in accordance with Indonesian government policies. For electric vehicles, a TKDN of ≥ 40% is required to qualify for the Government-Borne VAT incentive (PPN DTP), thereby making the price of electric buses more competitive.