February 17, 2026

The Blind Spots in Electric Two Wheelers Policy and Efforts to Reduce Transport Emissions

By Kemal Fardianto, Senior Transport Associate ITDP

Let us be clear about one thing: reliable, high-frequency public transportation services are the most fundamental solution to addressing inefficiency and disorder in urban mobility in Indonesia. However, time is no longer on our side. The window of opportunity to take corrective action and prevent worsening climate damage is rapidly narrowing.

Urban areas, which account for approximately 60–701 percent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, are increasingly affected by deteriorating air quality, with significant economic and public health consequences. The healthcare costs associated with air pollution alone are projected to reach up to Rp417 trillion annually by 20302. This underscores that expanding access to public transportation, along with its supporting infrastructure, is an essential step toward reducing vehicle emissions in cities. However, such efforts must be complemented by additional measures that directly target the largest sources of emissions.

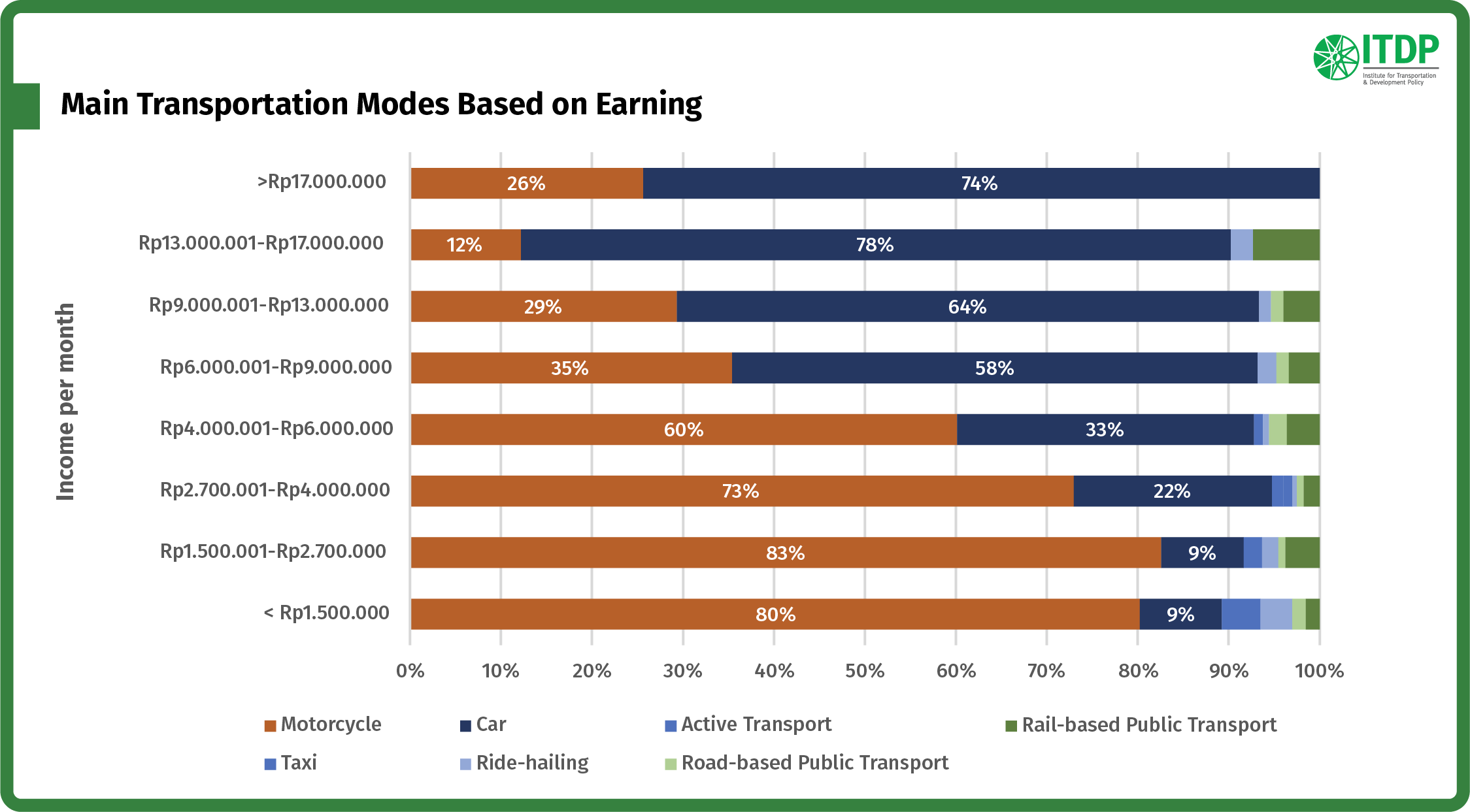

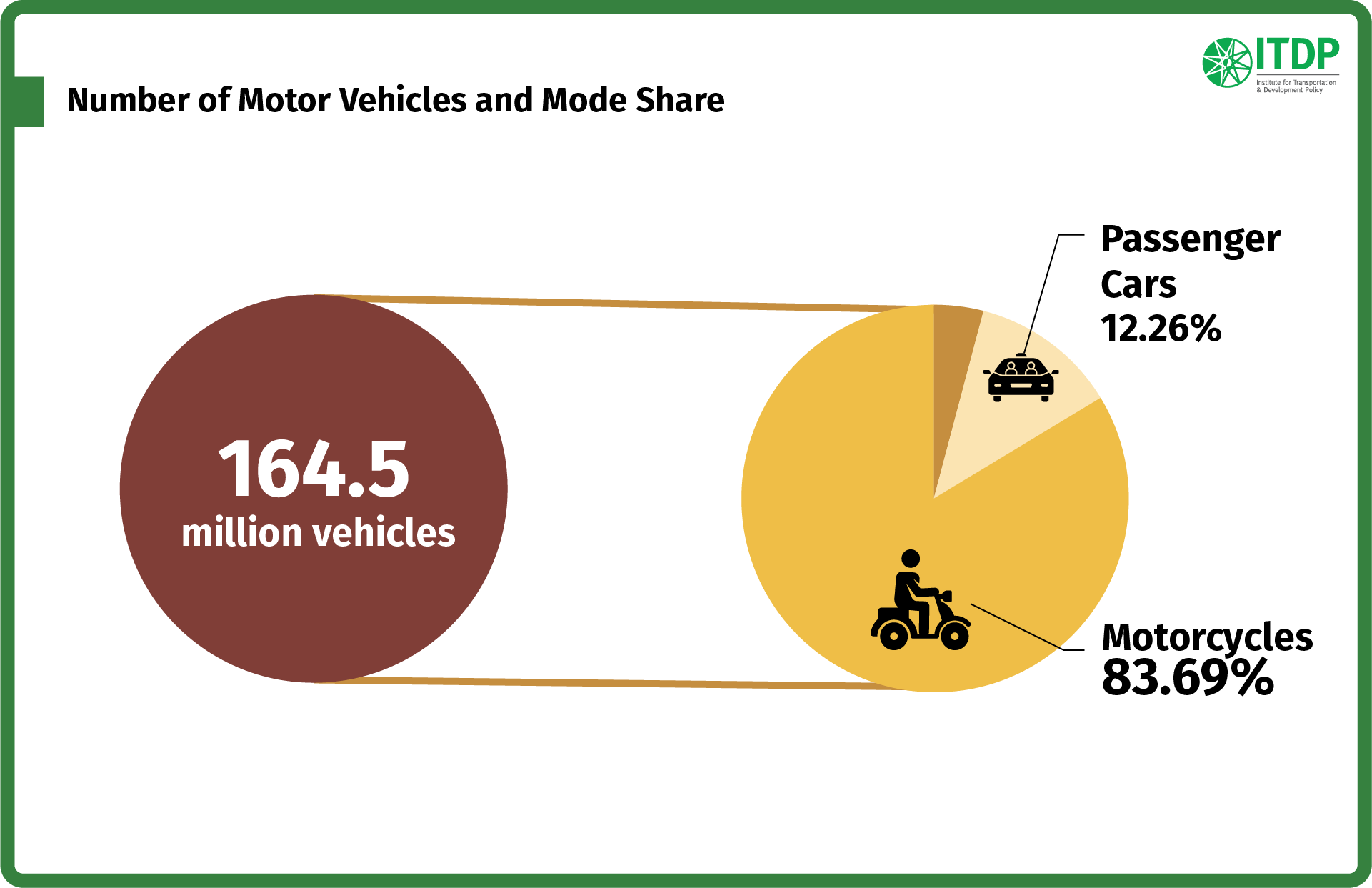

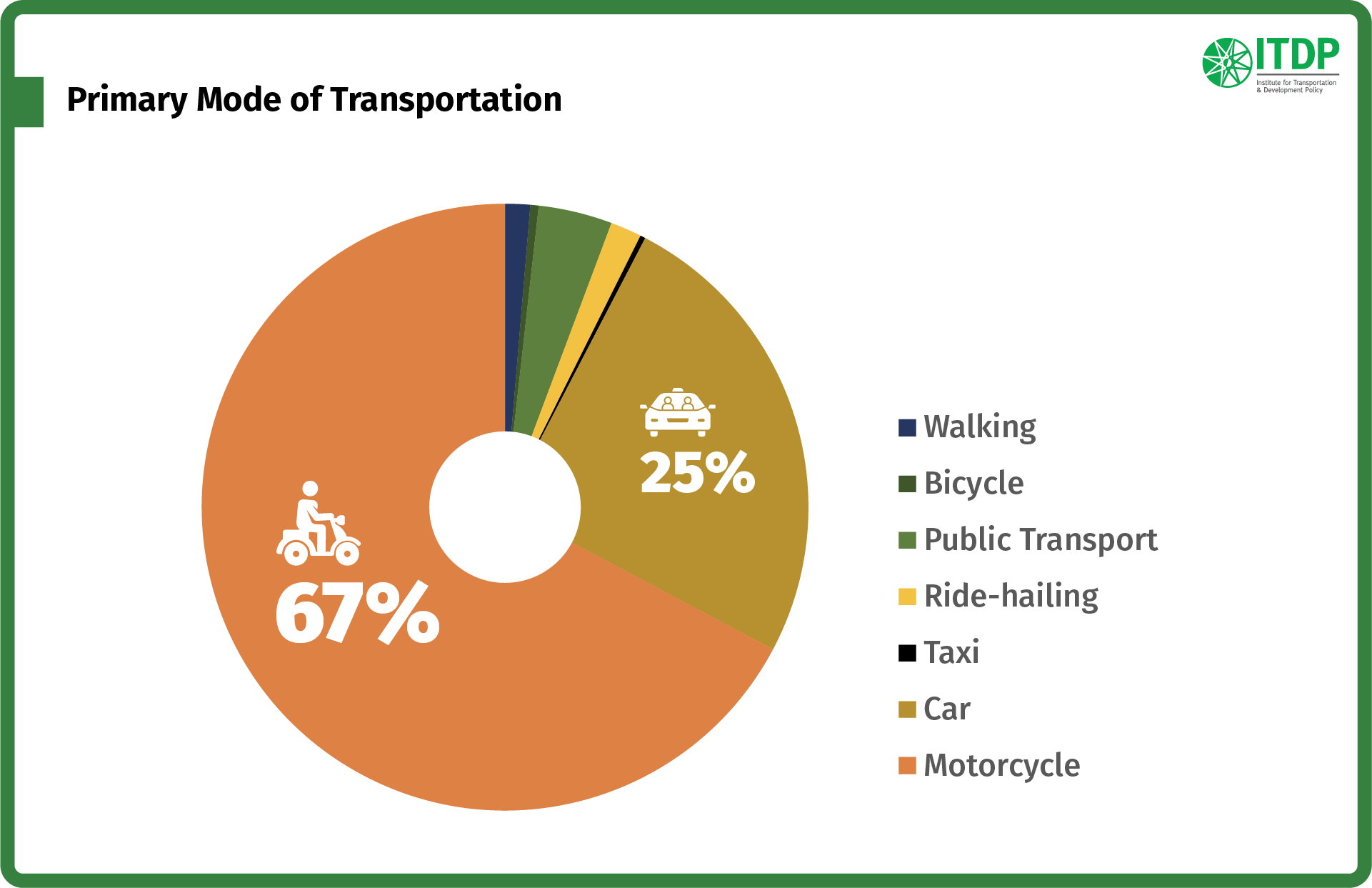

The dominance of motorcycles, which account for 80 percent of land transport modes, makes accelerating the transition from gasoline-powered to electric two wheelers a strategic step in advancing urban transport decarbonization efforts.

Motorcycles Remain as a Mainstay of Urban Mobility

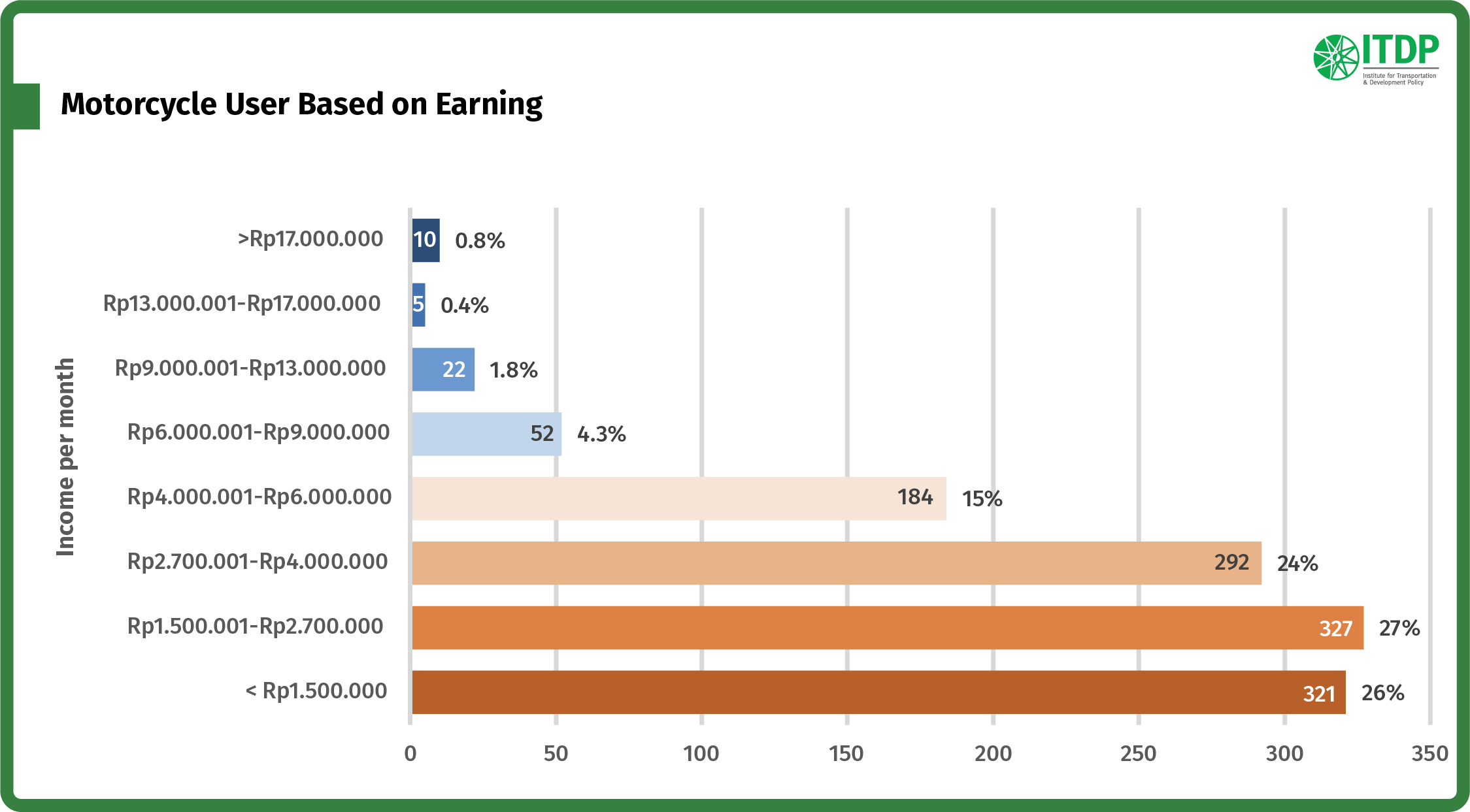

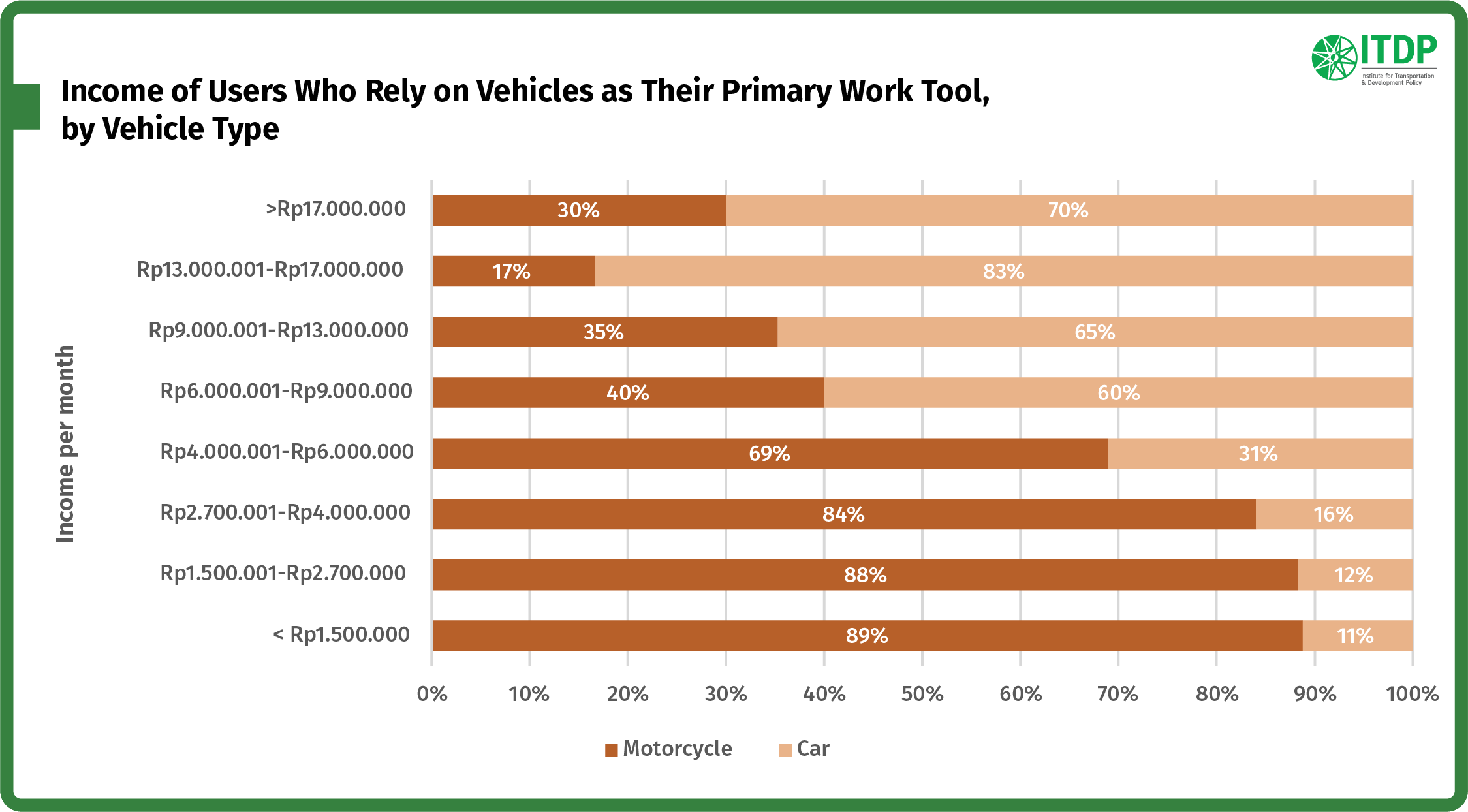

As of now, motorcycles continue to serve as the backbone of mobility, with two out of three urban residents relying on them as their primary mode of transportation, and for many, even as a means of livelihood3. More than 80 percent of individuals earning less than Rp2.7 million per month depend on motorcycles to sustain their income. Given their relative affordability, ease of access, and widespread use, the electrification of two wheelers (motorcycles) is crucial to advancing urban transport decarbonization. Strategies that overlook this reality risk failing to achieve the scale and impact required.

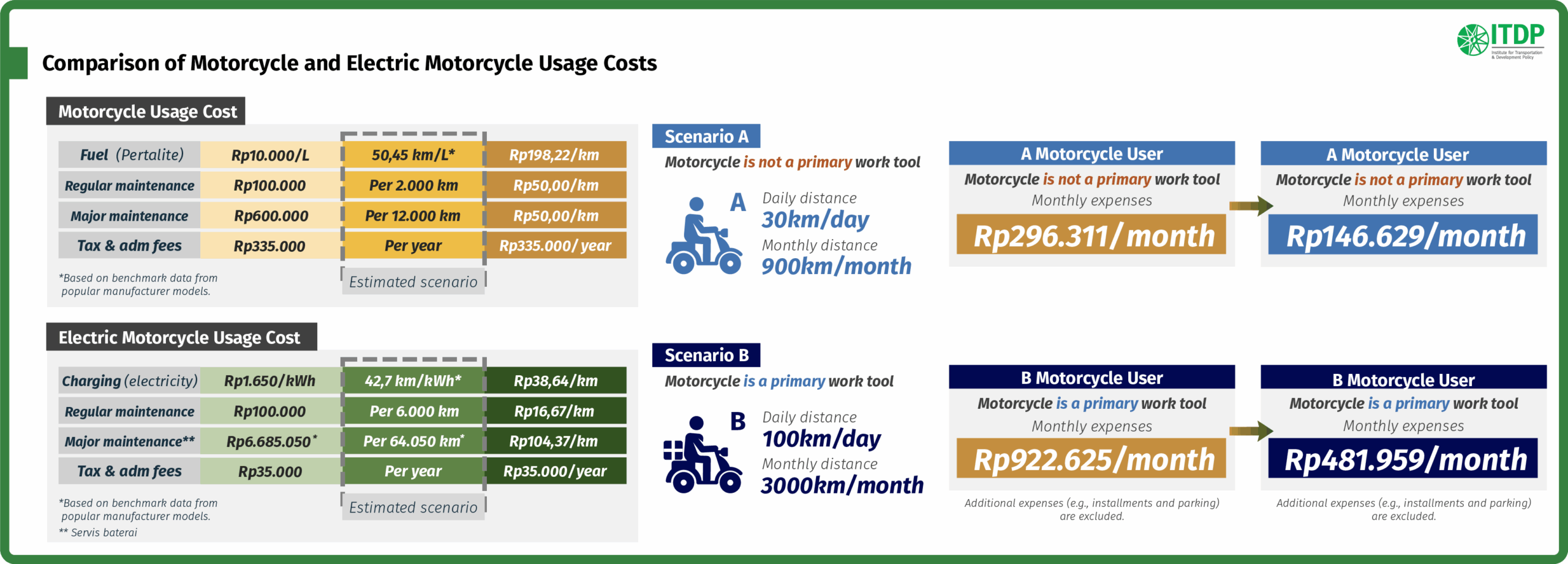

Despite the convenience they offer, motorcycles do not necessarily translate into significant transportation cost savings, particularly for those who rely on them for income. For workers earning between Rp4–6 million per month and traveling more than 100 kilometers per day, transportation expenses can consume up to a quarter of their income. This financial burden is even heavier for lower-income groups.

Amid rising transportation costs that continue to strain household finances, electric two wheelers offer a measure of relief. Various studies indicate that switching to electric two wheelers has the potential to significantly reduce operational expenses.

According to ITDP’s analysis, the transition to electric two wheelers could reduce transportation costs by up to 49%4 for daily users (±30 km per day) and up to 52% for those who rely on motorcycles as their primary work tool (±100 km per day).

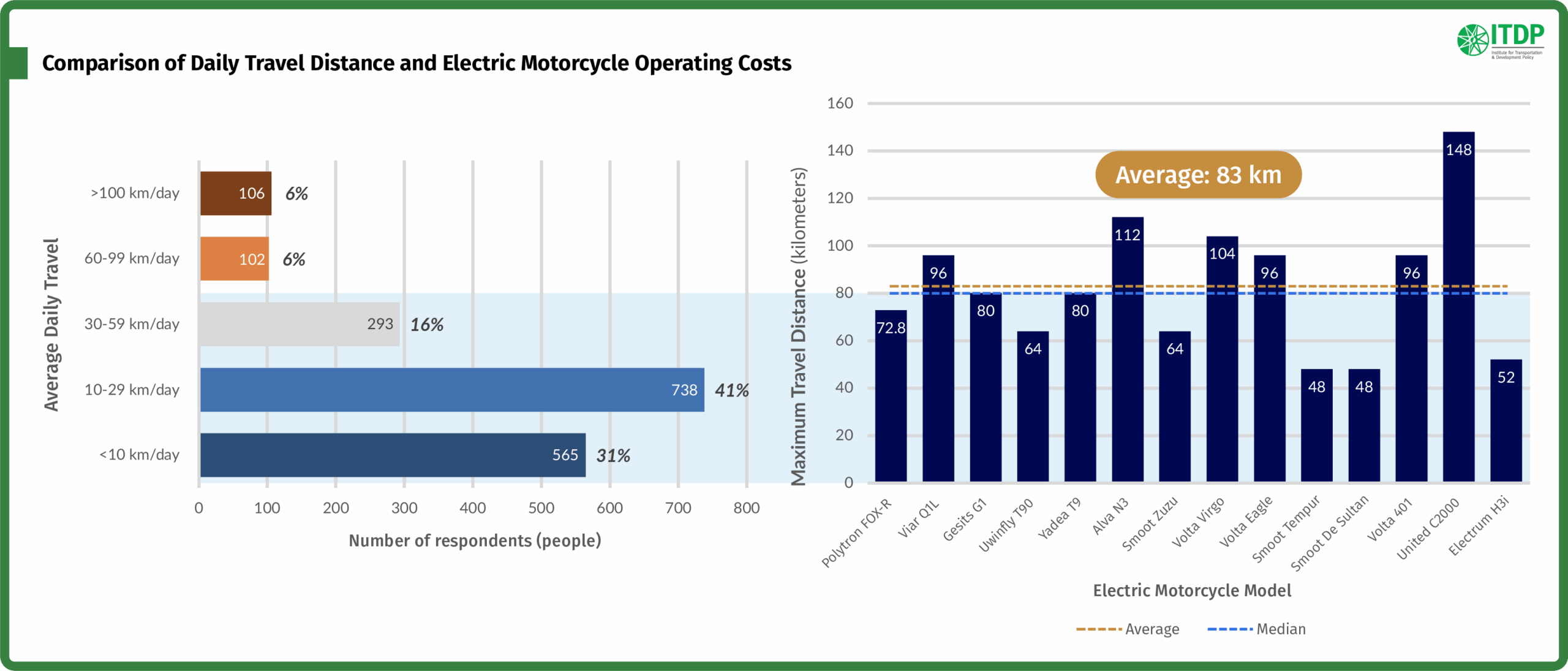

Hindrance to the Electric Two Wheelers Transition in Indonesia

New solutions rarely come without challenges. However, contrary to widespread public perception, the primary barriers to electric two wheelers adoption do not lie in the vehicles’ technological capabilities. Although performance varies across models, the average battery range of electric two wheelers currently available in the Indonesian market has reached around 80 km on a full charge. When compared with travel behavior data, this range is sufficient to meet more than 88 percent5 of daily mobility needs without the risk of running out of power mid-journey. In other words, from a technical standpoint, electric two wheelers are already capable of serving as reliable daily transportation.

The key to accelerating the transition to electric two wheelers lies in the availability of charging point infrastructure that does not disturb daily mobility activities. The fact that electricity has reached the majority of Indonesia’s households6 means home charging should have been the most logical solution to answer this need.

Unlike refueling at gas stations or charging at public facilities, which often requires waiting in long queues, home charging tends to be more efficient as it makes use of downtime when the vehicle is not in use—particularly at night.

Within this framework, public charging infrastructure functions as a complement rather than the primary backbone of the system. This balance is crucial. When most charging needs can be met at home, the government can avoid excessive investment in public charging stations while improving overall system efficiency.

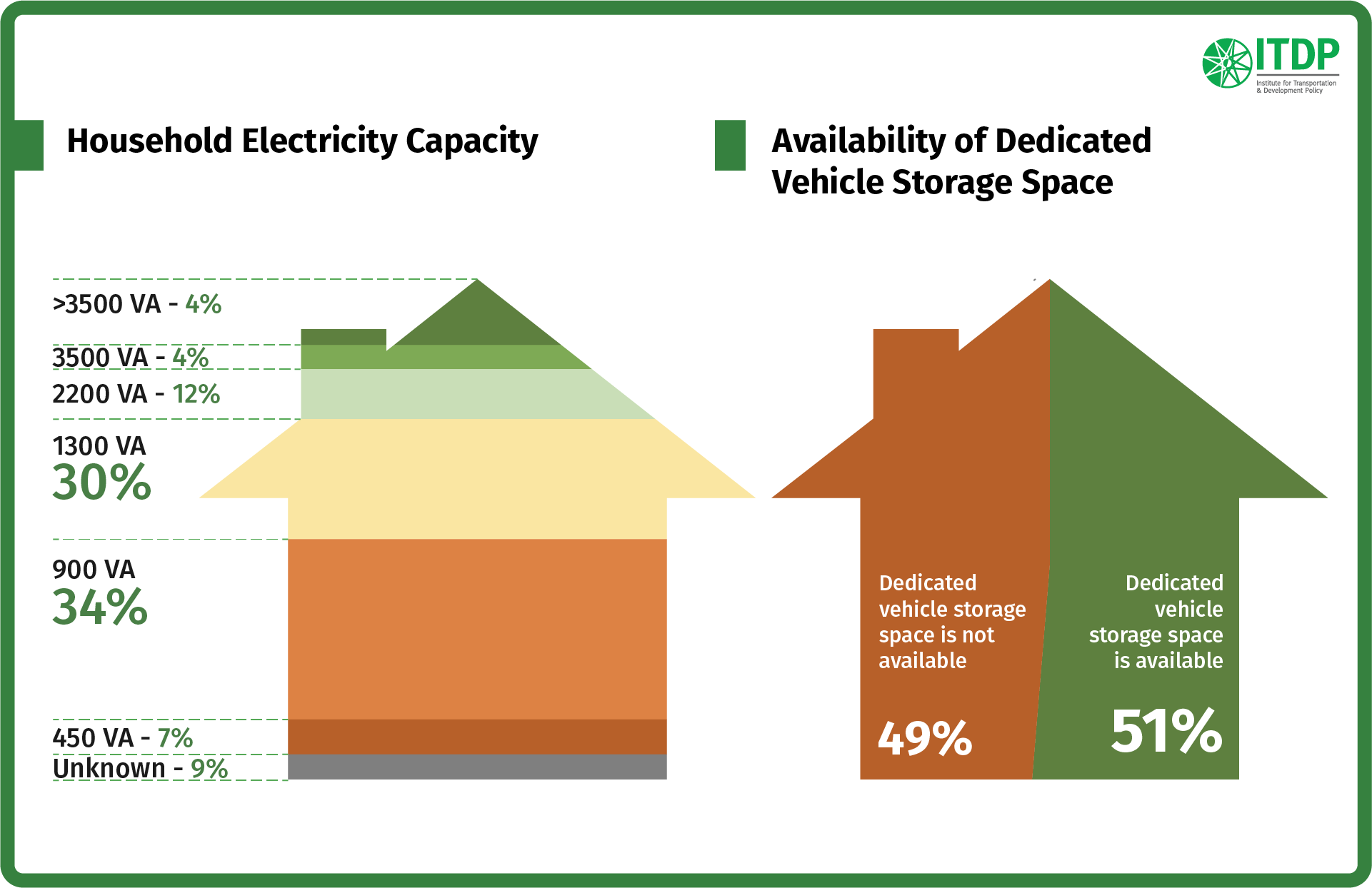

However, home charging will only be effective if supported by two key prerequisites: sufficient household electricity capacity and access to a parking space that allows for charging installation. At this point, the transition to electric two wheelers shifts from being a matter of technology to an issue of basic infrastructure governance. ITDP survey data indicate that these prerequisites have yet to be fully met.

Electricity requirements for charging electric two wheelers vary across models. However, conservatively, a minimum threshold can be set at 1,300 VA. Based on this assumption, around 41 percent of households still live in homes with electricity capacity that does not support two wheelers charging.

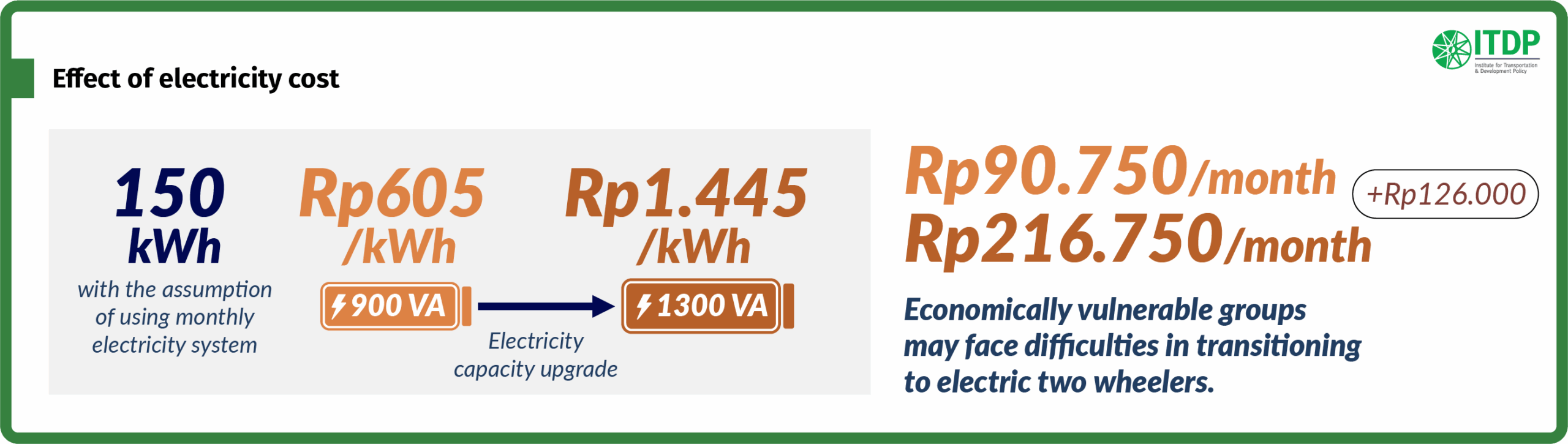

At first glance, the solution seems straightforward: upgrade household electricity capacity. Yet for motorcycle users who are highly cost-sensitive, this step is far from simple. Increasing capacity not only requires an upfront installation cost but also alters the monthly electricity tariff. For households currently using subsidized 900 VA connections, upgrading to 1,300 VA means exiting the subsidy scheme and facing a sharp increase in electricity bills—more than doubling for the same level of consumption7.

This consequence exists even before the cost-saving benefits of electric two wheelers can be fully experienced. In this context, upgrading the household’s electricity capacity can potentially be the first hindrance in adoption, especially for lower-income groups that rely heavily on motorcycles.

Another challenge arises from spatial constraints. Nearly half of the population lacks access to parking spaces that are either available or suitable for installing charging equipment, including electrical outlets and dedicated circuits. This group includes residents of low-cost flats, apartments, and boarding houses, where access to parking facilities is often beyond individual control.

The issue becomes even more complex for those living in collective housing such as apartments, where parking management lies beyond residents’ control. The decision to switch to an electric two wheelers often depends on the availability of charging outlets with sufficient capacity in parking areas. Even when such facilities exist, users must still obtain permission and reach agreements on electricity metering and payment, particularly when meters are managed by building management or property owners.

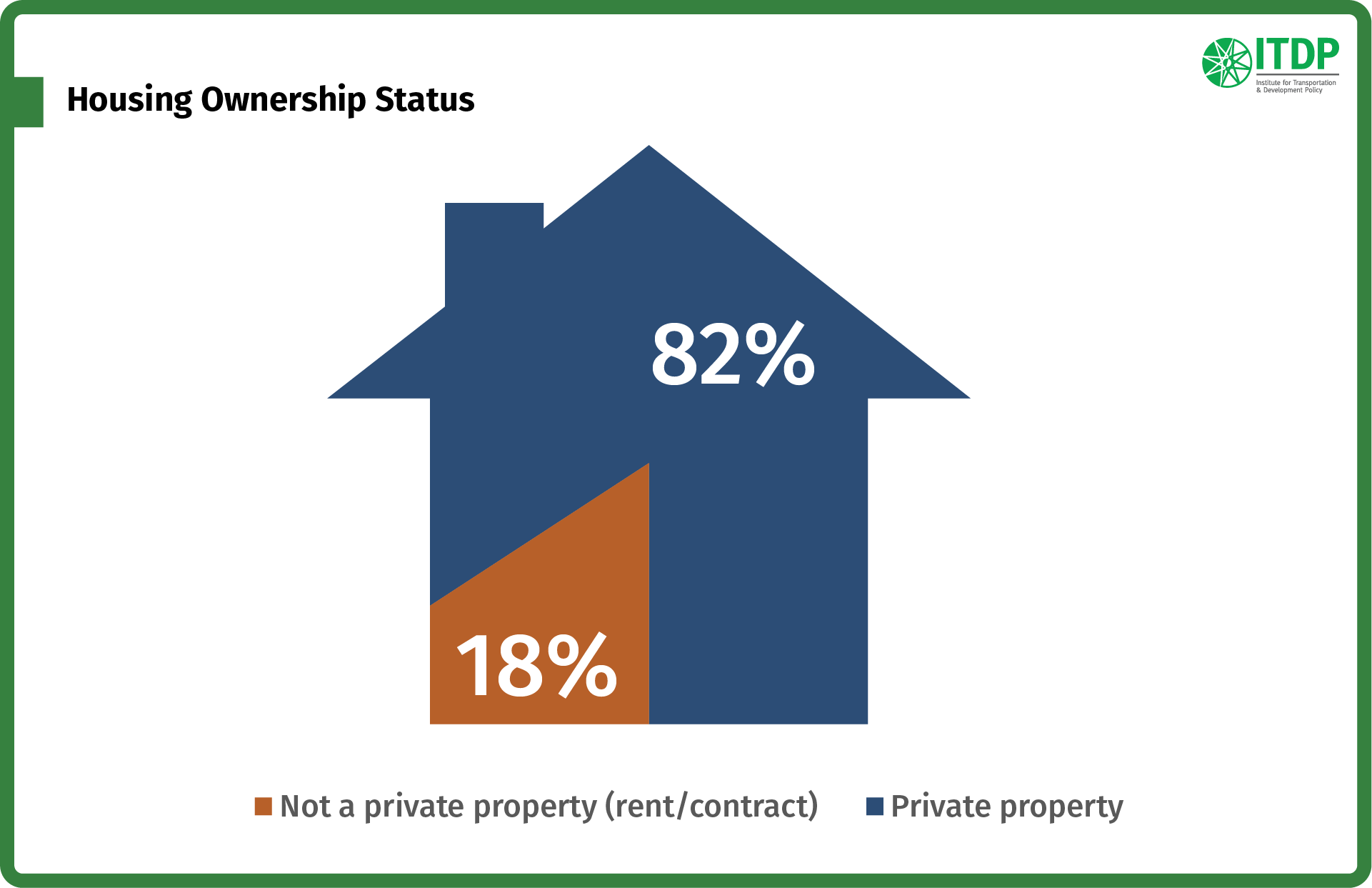

A similar situation applies to tenants in landed rental housing. When a residence is not equipped to support electric two wheelers charging and requires electrical adjustments, the landlord’s approval becomes a prerequisite. Survey data indicate that around 18 percent of the population lives in rental housing—a group with limited agency in determining changes to their homes’ basic infrastructure.

Blind Spots in Strategy and Policy Directions That Need Correction

ITDP’s study shows that charging remains the primary concern among prospective users, largely due to limited understanding of the prerequisites and processes involved in home charging. The study’s modeling further demonstrates that improving access to home charging not only increases adoption interest but also shapes the perception of electric two wheelers as practical and beneficial technology, thereby strengthening individuals’ intention to switch.

These findings point to a fundamental issue the government must confront if they are serious about positioning electric vehicles as a key instrument of decarbonization.

What hinders the transition to electric two wheelers is not users’ reluctance but rather infrastructure and policy constraints that make the shift difficult—if not impossible—to undertake. When around 41 percent of the population faces structural barriers, achieving large-scale adoption of electric two wheelers becomes unlikely.

To date, policy responses have largely centered on expanding public charging infrastructure, in line with the national roadmap for charging network development (Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Decree No. 24.K/TL.01/MEM.L/2025). While this approach is important, it has yet to address the core foundation of the transition: home charging. Without complementary strategies, expanding public infrastructure risks increasing pressure on the grid and investment needs—an option that is far from ideal amid fiscal constraints.

What is needed is a recalibration of policy direction. First, Indonesia should adopt a national strategy to expand access to home charging, including technical standards, safety guidelines, and coordination with electricity providers. Second, targeted support for low-income and vulnerable groups is essential. This could take the form of subsidies for electricity capacity upgrades, assistance for home assessments and charging installation, shared charging solutions in communal housing, and more accommodative and adaptive electricity tariff schemes—particularly given that upgrading connection capacity currently results in higher per-kilowatt-hour tariffs. Large-scale electrification of motorcycles will not be achieved if home charging continues to be treated as secondary. It must be recognized as a prerequisite for a clean, equitable, and sustainable urban transport transition.

In 2025, ITDP launched a questionnaire-based survey examining the influence of charging infrastructure availability on electric vehicle adoption. Using a sampling approach and subgroup segmentation, the survey engaged more than 1,800 respondents across four metropolitan areas in Indonesia to explore public perceptions and vehicle-use patterns in the context of charging infrastructure development. The survey forms part of ITDP’s ongoing study, with a primary focus on assessing infrastructure-related barriers to electric vehicle adoption in Indonesia. The survey analysis is intended to inform the formulation of actionable charging-infrastructure development strategies for relevant stakeholders.

Footnotes:

- UN-Habitat. (n.d.). The Strategic Plan 2020-2023. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-09/strategic_plan_2020-2023.pdf

- Rachmansyah, G. (2024, September 10). Biaya Kesehatan Diprediksi Tembus Rp417,1 Triliun Imbas Polusi Udara.https://economy.okezone.com/read/2024/09/10/320/3061200/biaya-kesehatan-diprediksi-tembus-rp417-1-triliun-imbas-polusi-udara?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- ITDP Indonesia. (2025). ITDP Survey 2025.

- Transportation costs in this context refer only to the operational expenses shown in the image and do not include other costs such as vehicle ownership capital costs, purchase installments, parking fees, or additional expenditures.

- Daily urban mobility needs are derived from survey sample data across four metropolitan areas.

- Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS). (2025). Persentase Rumah Tangga menurut Provinsi dan Sumber Penerangan Utama dari Listrik. https://www.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/NzcyIzI=/persentase-rumah-tangga-menurut-provinsi-dan-sumber-penerangan-utama-dari-listrik.html

- The calculation uses the electricity tariff (IDR/kWh) for the fourth quarter of 2025, sourced from PLN.