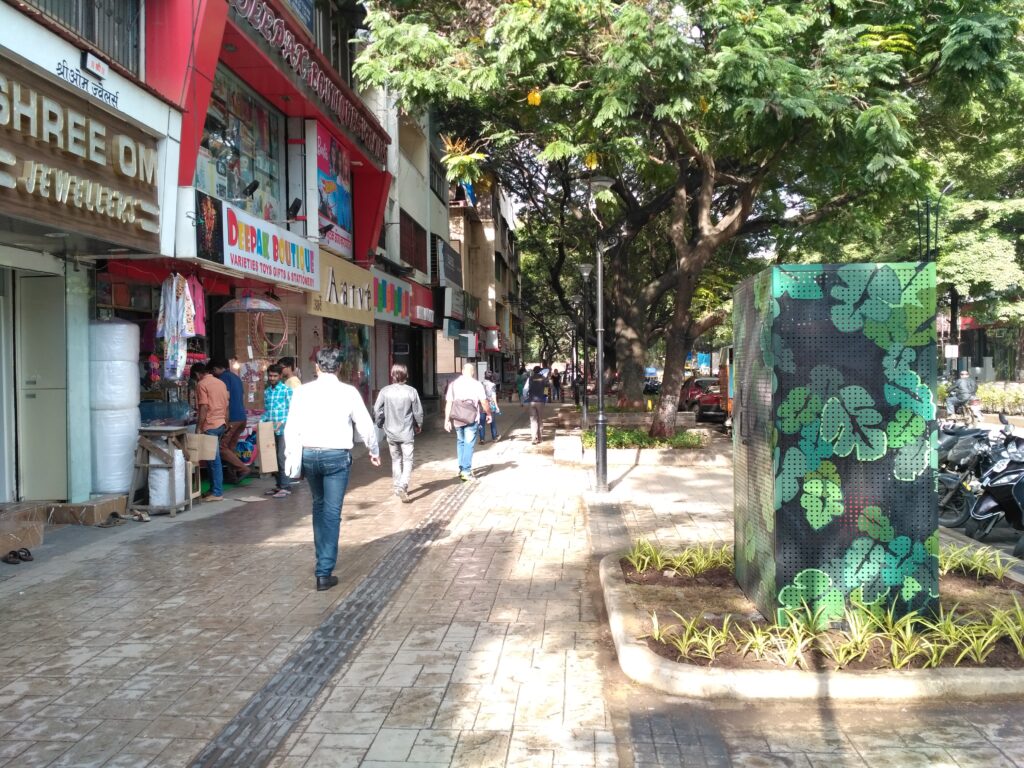

A scene from a trial run to test the proposed design for the pedestrian plaza in T.Nagar, which was a hit amongst the public.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a splash two years ago when he announced a plan to tackle his nation’s expected rapid urbanization. 100 smart cities would bloom across the world’s second most populous country, with the first 20 serving as “lighthouses” that would inspire the estimated 4,000 cities that are home to one-third of the population – a share that is expected to climb to over 40% by 2030.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a splash two years ago when he announced a plan to tackle his nation’s expected rapid urbanization. 100 smart cities would bloom across the world’s second most populous country, with the first 20 serving as “lighthouses” that would inspire the estimated 4,000 cities that are home to one-third of the population – a share that is expected to climb to over 40% by 2030.

Enshrined in a flagship program called the Smart Cities Mission, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs launched a city challenge with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. In an effort to change entrenched corruption at the municipal level, cities would compete against each other to deliver the best proposals for a share of a whopping US$15 billion allocated by parliament.

As the ministry’s Secretary for Smart Cities, Sameer Sharma is at the nerve center of this massive undertaking. ITDP spoke with him about how India has refined the smart city concept.

ITDP: The theme of the recent MOBILIZE Santiago conference was “just and inclusive cities become the new normal.” How do Indian cities measure up to this ideal?

Sameer Sharma: India’s Smart Cities Challenge invited cities to propose developments that transform existing areas, including slums, into better-planned ones, or explore the potential for new development of greenfield sites outside city boundaries to accommodate a growing urban population. Apart from setting the core objective of improving basic hard and soft infrastructure and introducing smart solutions to Indian cities, the Smart Cities Mission set out a broader ambition to “improve quality of life, create employment and enhance income for all, especially the poor and the disadvantaged, leading to inclusive cities. ”

Contrary to the assumption that smart cities project would only be taken up in affluent areas, most cities have chosen neighbourhoods with substantial slum areas, dense and ill-provisioned inner city zones, and railway stations. For example, slum redevelopment forms a major component of the Ahmedabad plan. The redevelopment proposal for Wadaj slum includes housing for 8,000 slum dwellers and development of a community centre, schools, aanganwadis [mother and child care center], and complete infrastructure improvement including open spaces in the area. 12 out of the 20 lighthouse cities have cumulatively proposed affordable housing projects offering around 55,000 housing units.

ITDP: What do you see as the role that the national government should play in helping cities achieve these goals?

Sameer Sharma: The London School of Economics studied India’s Smart City Challenge and found that it was perceived as being instrumental in promoting a degree of agency and flexibility for city governments and encouraging them to take initiative while operating within an established federal framework. Many respondents felt that the competitive component of the Smart Cities Challenge allowed cities considerable space to develop their proposals. This greater flexibility was also reinforced by the encouragement to identify financing mechanisms independent from state or national sources.

The Smart Cities Mission was perceived as a localized program that gave city governments the space to shape their city’s proposals without much intervention from the central government. This can be attributed to the center’s capacity building initiatives, and the competitive format itself that generated enthusiasm and involvement at the municipal level. On the whole, the central government’s role in the competition phase appeared to be limited to competition guidelines and capacity building exercises through which it shared best practices, ideas and modes of financing projects. Overall, the Smart Cities Challenge signaled a shift in the balance of power between city, state, and central government.

How do you define smart cities? What are the key things that make a city smart?

A smart city has a different connotation in India than in, say, Europe. Even in India, a smart city means different things to different people and the conceptualization of a smart city varies from city to city, state to state, and region to region, depending on the level of development, willingness to change and reform, and resources and aspirations of the city residents. No single definition can capture the diverse conceptualizations of city residents, especially in the unique Indian culture containing dynamic, diverse, and contextual rules in use. A survey by the Center for Study of Science, Technology & Policy found that there are nearly four-dozen ways of defining a smart city. Therefore, the Indian Smart City Mission did not start with a definition of a smart city but invited cities, through a competition, to define their idea of “smartness” and the pathway to achieve it.

As a result, drawing on the Smart City Challenge proposals, the following definition has been derived: The Indian Smart Cities Mission adapted and redefined the global discourse around ‘Smart Cities’ to create its own unique take on a ‘Smart City’, one that features but is not centered exclusively on technology and includes a strong emphasis on area-based development, citizen preferences, and basic infrastructure and services.

What cities around the world are you most interested in today? Who is doing innovative work in your field?

Several cities are doing remarkable work in the field of ‘smart’ and ‘sustainable’ urban development. I am impressed with Copenhagen on walkability, Adelaide for placemaking, integrated command and control centers in New York and Berlin, how Oakland has tackled liveability, Bilbao’s strategies for urban renewal, and Barcelona’s overall urban transformation.

Is the challenge approach fueling innovation within Indian Cities?

An important innovation in the competition process was that it allowed state governments to select cities to participate, while municipal governments had to demonstrate enthusiasm in order to be successful. A second innovative development of the Smart Cities Challenge was that it sidestepped the issue of forcing state governments to devolve funding by allowing convergence of funding from other schemes. By requiring agency and alignment from both city and state, the Smart Cities Challenge encouraged cooperation and led to increased municipal initiative while allowing the continued role of the state government.

This interview is the part of the MOBILIZE Santiago Speaker Series. In this series, we will feature interviews with speakers and researchers from VREF’s Future Urban Transport where they will discuss their work in sustainable transport and reflecting on MOBILIZE Santiago’s theme: Just and Inclusive Cities Become the New Normal. To learn more about MOBILIZE Santiago and next year’s summit in Dar es Salaam, visit mobilizesummit.org.

This interview is the part of the MOBILIZE Santiago Speaker Series. In this series, we will feature interviews with speakers and researchers from VREF’s Future Urban Transport where they will discuss their work in sustainable transport and reflecting on MOBILIZE Santiago’s theme: Just and Inclusive Cities Become the New Normal. To learn more about MOBILIZE Santiago and next year’s summit in Dar es Salaam, visit mobilizesummit.org.