July 07, 2024

Let’s Reclaim the City Space!

By Syifa Maudini, Transport Assistant ITDP Indonesia

The concept of restricting the use of private cars and motorcycles appears challenging to envision in cities that heavily depend on these modes of transportation. Understandably, for residents, limiting cars and motorcycles appears to take away the “convenience” of getting around the city.

In Jakarta, the number of motorized vehicles continues to increase. From 2020 to 2023, the number of motorized vehicles reached 662,000 units [1], with a usage rate of 81% (Jakarta Provincial Transportation Agency, 2023). It is no surprise that residents in Jakarta now have to endure hours of traffic jams, even taking 45 minutes to cover just 3 km! The phrase “aging in traffic” is becoming a daily reality for residents. Ironically, over 85% of Jakarta is covered by Transjakarta’s public transportation network (BRT and non-BRT, including microtrans)(ITDP Indonesia, 2022). The development of public transportation has also been accompanied by increased accessibility to the stopping point through the revitalization of pedestrian paths and the construction of bicycle lanes. So, what still causes people to rely heavily on private cars and motorcycles and be reluctant to use public transportation?

When Space for Humans Becomes Space for Motorized Vehicles

Excessive provision of parking space is one of the reasons. Private motorized vehicle users begin and end their trips by parking their vehicles. The popular theory is that as the number of motorized vehicles increases, more parking spaces are needed.

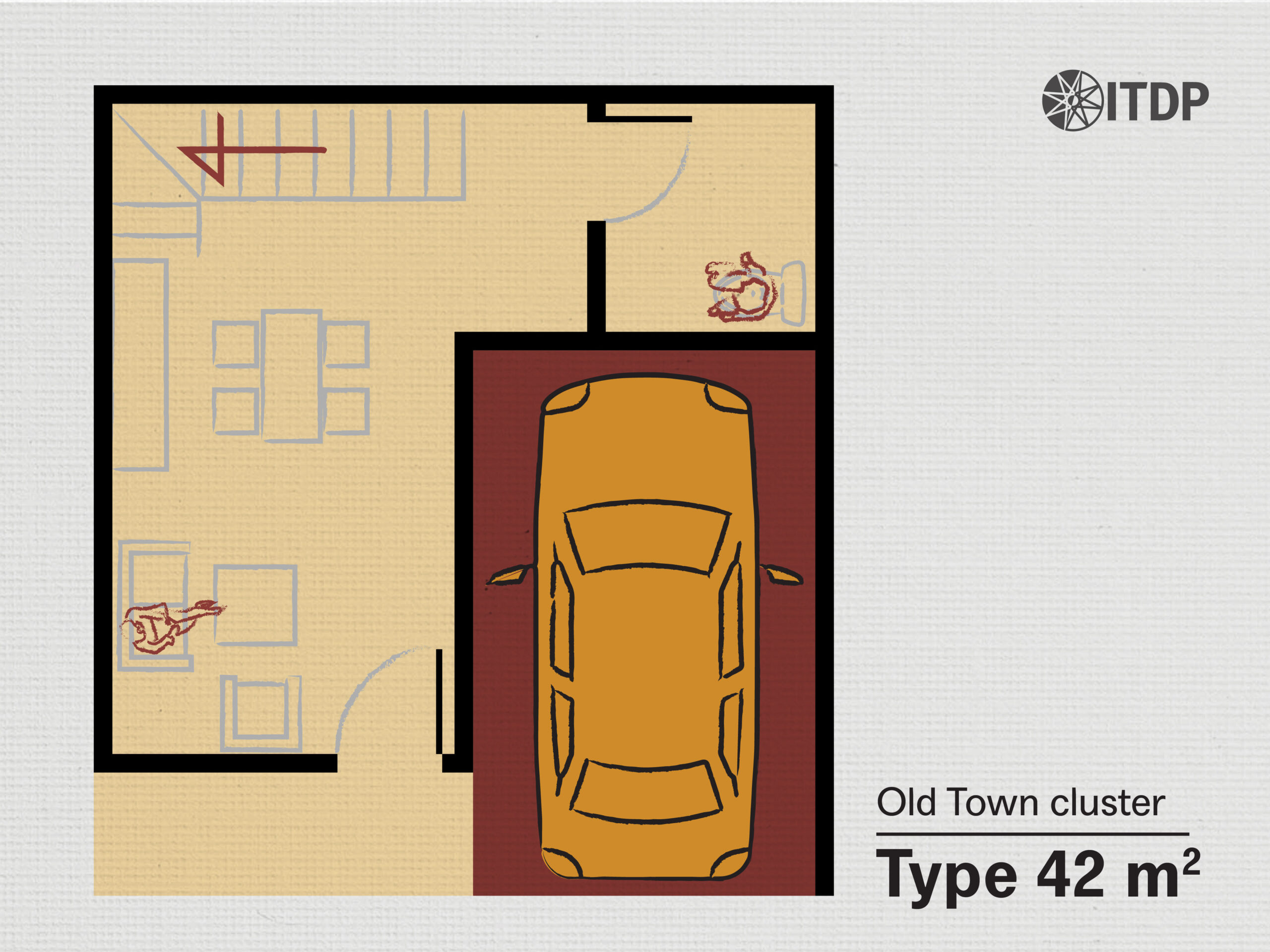

However, if the solution to the excessive use of private motorized vehicles is to add more parking spaces, won’t this lead to city land being dominated by parking lots?

Continuing to add parking spaces is the same as continuing to increase the number of vehicle lanes, forming an endless cycle of dependence on motorized vehicles [2]. Moreover, the ease of finding parking also contributes to the decline in public transportation services and usage.

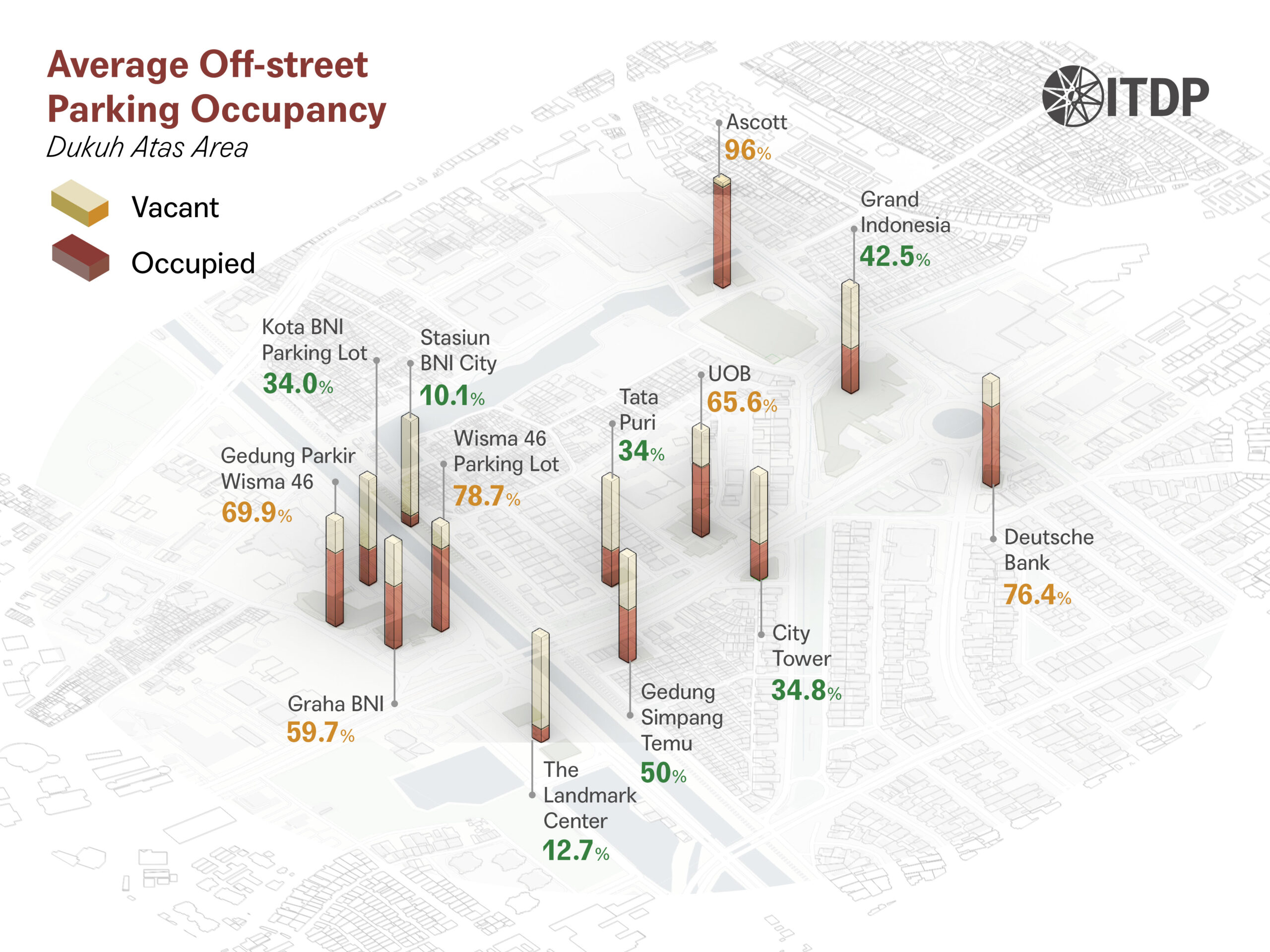

In the Dukuh Atas area, for instance, there are still approximately 30,000 off-street parking spaces despite being served by four high-quality mass public transportation modes. According to an ITDP Indonesia survey in 2023, the occupancy of these parking spaces only reached less than 80% per day on weekdays. Additionally, in the Dukuh Atas area, besides the ease of accessing off-street parking, on-street parking, which is increasingly spreading, is even easier to find, forming illegal parking pockets that use pedestrian paths and bicycle lanes. ITDP Indonesia (2021) noted that the number of cars and motorcycles parked illegally in the Dukuh Atas area is nine and five times higher than those parked legally. It’s no wonder public transportation users, pedestrians, and cyclists still have to compete for road space in Dukuh Atas.

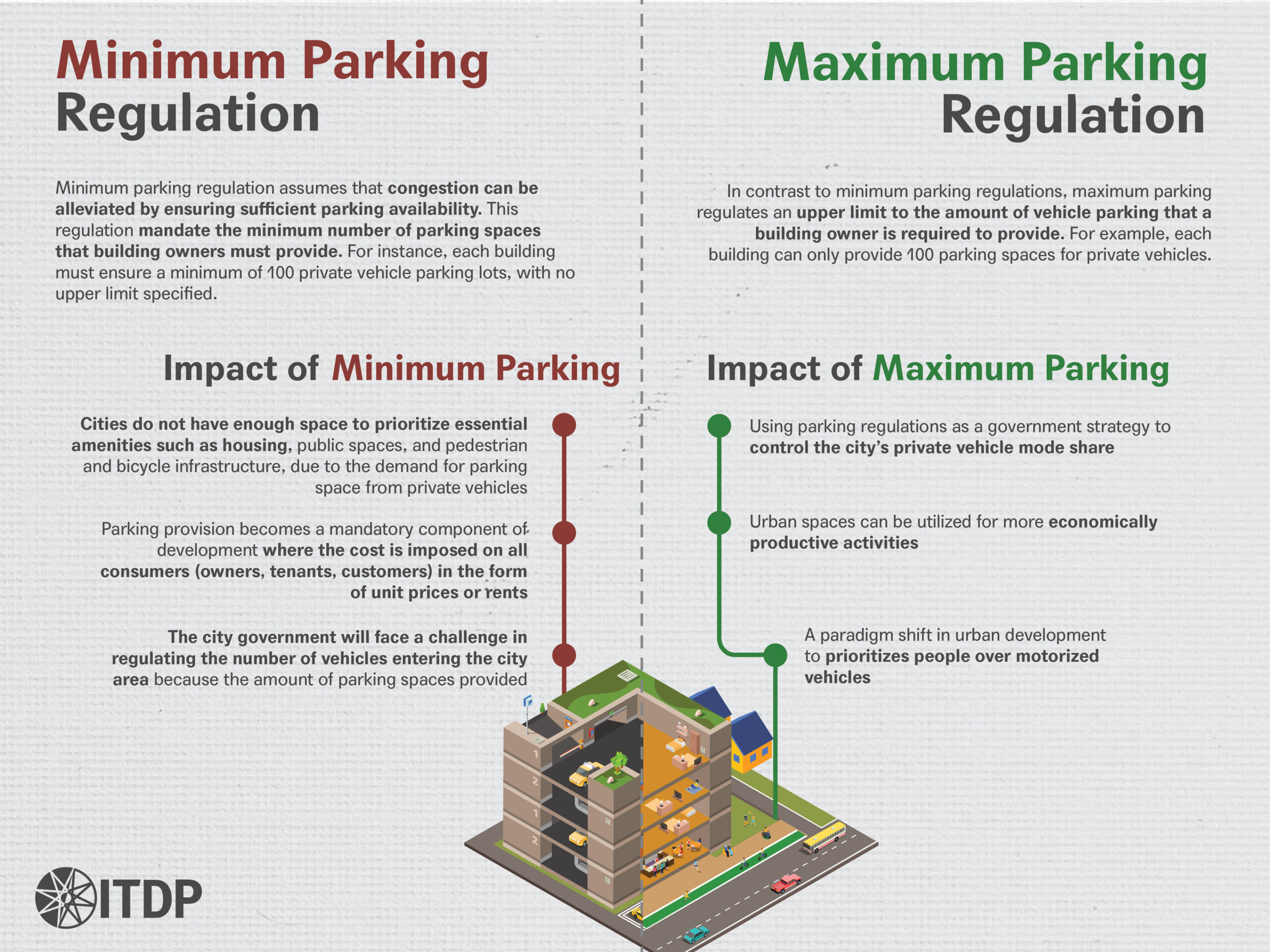

These conveniences are not solely due to the lack of strict and regular law enforcement but are also supported by the existing parking policies. Specifically for buildings, land/building owners must provide off-street parking by meeting the minimum required amount. For instance, a trade center with an area of 1,000 m² must allocate at least 59 parking spaces [3]. This means that land/building owners are encouraged to provide no less than this number or even more.

Reimagining City Space for People

Since 2017, ITDP Indonesia has advocated how parking spaces can be repurposed for more economically and socially valuable uses through activities like Park(ing) Day, transforming parking areas into discussion spaces [8] and play areas [9]. Several buildings in Jakarta have already converted parts of their parking spaces for businesses, both pop-up and permanent. The 2023 World Bicycle Day event in Ayodya Park also demonstrated that with just three car parking spaces, more than 50 bicycles could be accommodated, highlighting the efficient use of space to attract more visitors.

Parking spaces, especially inside buildings, also have significant potential for providing affordable housing in the city center. Amidst the scarcity and high land prices in the city center, which forces residents to commute from satellite cities to downtown Jakarta, cramming into public transportation, 30,000 parking spaces with a total area of approximately 265,000 m² in Dukuh Atas, with land prices exceeding Rp20,000,000 per square meter, could provide around 7,360 housing units of 36 m² each (ITDP Indonesia, 2021)!

It’s not merely theoretical, parking reform with parking space restrictions in Mexico City in 2017 reduced off-street parking by 21% in constructed buildings [4]. This resulted in up to a 15% increase in space available for human activities within the city.

ITDP Indonesia, supported by the UK government through the Future Cities UK Partnering for Accelerated Climate Transitions (UK PACT) program, also released a study titled “Jakarta Parking Reform.” This study provides guidance and recommendations for the Jakarta Provincial Government in reforming parking policies. The study also provides an overview of the gap between policy and implementation, as well as findings that strengthen the urgency of parking reform in Jakarta.

Time for Parking Reform

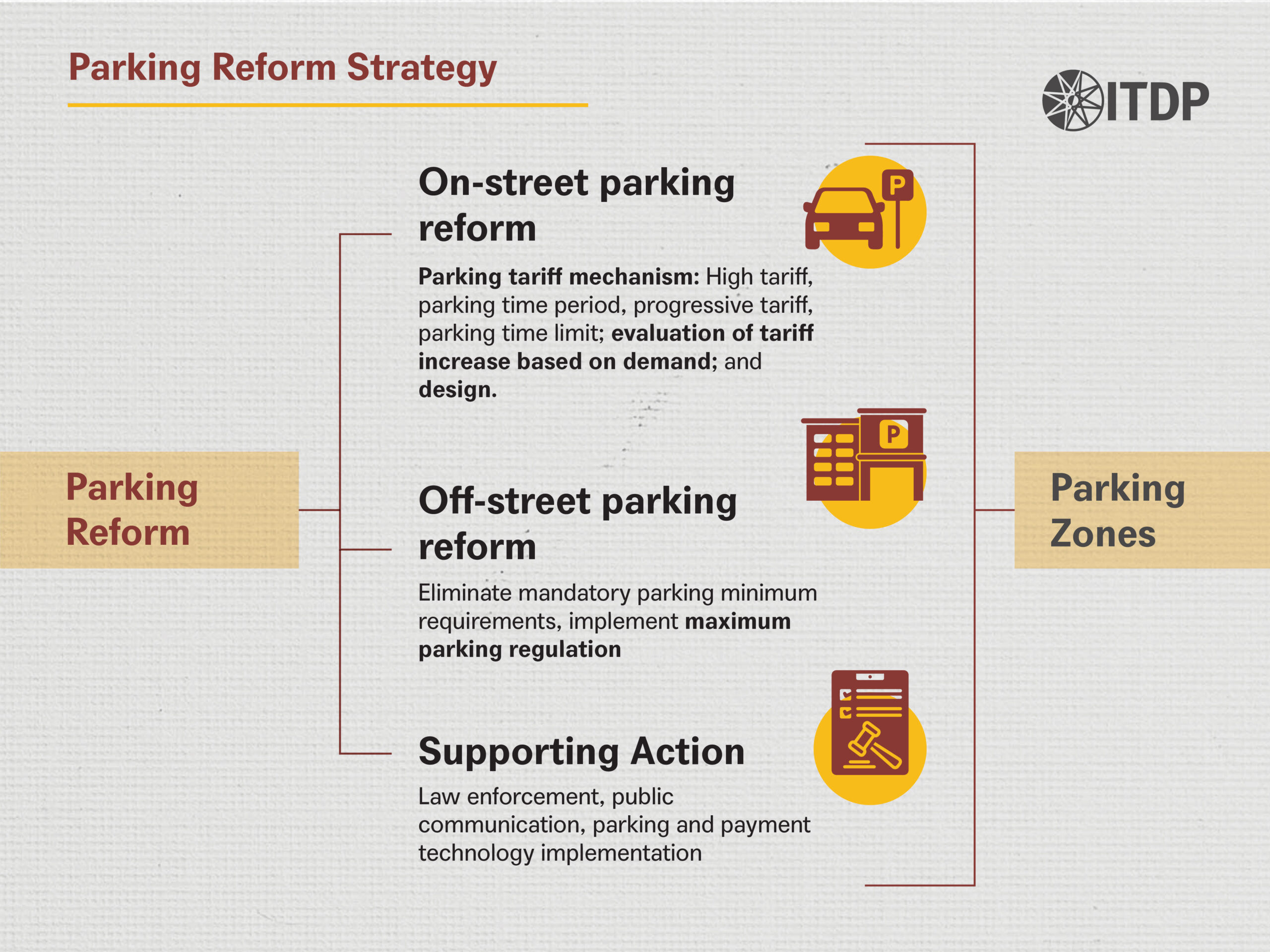

Reforming parking policies by controlling parking provision is primarily aimed at enhancing city quality by providing better public transportation services, high-quality pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, and decent housing in the city centers. Parking reform needs to address both types of existing parking facilities, on-street and off-street, simultaneously.

Common controls for on-street parking include implementing high tariffs with specific mechanisms, often utilizing technology [5]. These tariffs should be regularly evaluated based on usage levels. When the usage is high, tariffs are increased so that users move to parking locations with lower tariffs. Reforming on-street parking can ensure better road safety, smoother traffic flow, and easier access to parking spaces. In Mexico City’s Polanco district, after the EcoParq program ran for three years, the average time to find an on-street parking space improved by 75%. A single parking space that accommodated only 3.5 cars per day now serves between 4.5 to 5.5 cars per day (ITDP Mexico, 2013).

Meanwhile, the most common control for off-street parking involves limiting parking space provision through parking maximum requirements [6]. It is challenging for developers/landowners to meet specific minimum parking requirements. An ITDP Indonesia survey (2023) in Dukuh Atas revealed that 6 out of 7 buildings provided parking spaces below the minimum requirement. Moreover, in densely populated urban areas, people tend to park in one place and then walk to nearby locations [7]. Without adding parking spaces, new buildings can provide shared parking with surrounding buildings, making current parking space use more optimal.

Reclaiming City Space

Over the years, humans have given up so much to motorized vehicles, making it difficult to envision city life without complete dependence on private cars and motorcycles for mobility. Before it becomes too late, city space reform through parking reform in Jakarta must happen to provide more space for people.

——————————-——————————-——————————-——————————-

References:

1. Badan Pusat Statistik. (2024). Provinsi DKI Jakarta Dalam Angka 2024.

2. Putra, Rahmad W. (2024). Mewujudkan Jalan Perkotaan yang Adil. ITDP Indonesia.

3. Keputusan Direktur Jenderal Perhubungan Darat Nomor 272/HK.105/DRJD/96 tentang Pedoman Teknis Penyelenggaraan Fasilitas Parkir

4. ITDP Mexico. (2021). Presentación: Más ciudad, menos cajones – Evaluación 2020.

5. ITDP. (2021). On-Street Parking Pricing: A Guide to Management, Enforcement, and Evaluation.

6. ITDP. (2023). Breaking The Code: Off-Street Parking Reform.

7. Barter, Paul. (2019). The Adaptive Parking approach to municipal parking policy. Reinventing Parking.

8. ITDP Indonesia. (2017). Park(ing) Day Jakarta 2017: Parking Space to People Space.

9. ITDP Indonesia. (2018). Park(ing) Day 2018: Mengambil Alih Ruang Parking Selama 60 Menit.

Read the document titled “Jakarta Parking Reform Guidelines.”