November 07, 2024

Jakarta’s Traffic Solution is Within Reach, But Who is Brave Enough to Take the Step?

By Carlos Nemesis, Urban Planning Associate ITDP Indonesia

We all know that congestion is driven by an overload of vehicles, and building more roads won’t solve the issue. Meanwhile, restricting private vehicle use—which numerous studies recommend as the best solution—has been repeatedly delayed despite nearly two decades of planning. With the increasing negative impacts on both the economy and public health, it’s time to take bold, concrete action, supported by careful planning to ensure targeted and effective implementation.

Expanding roads or building new ones will only trigger induced demand, leading to more vehicle trips. This phenomenon is easier to understand than it seems, as generally, more people will drive when it becomes faster and more convenient, especially when new roads are still empty. However, over time, newly constructed roads will also experience congestion, as seen many times before.

Jakarta is already on the right track, with notable progress in public transport development. The bus rapid transit (BRT) system serves 1.2 million passengers daily, along with various rail-based transport options like Commuter Line, MRT, and LRT. Jakarta even allocates IDR 4 trillion each year for public transport subsidies (PSO). However, focusing solely on providing public transport is not enough to tackle the core issue of traffic congestion and air pollution. Supporting policies are needed to shift people from private vehicles to public transport, considering that the current mode share of public transport use is only at 10%, far below the 55% target for 2045. Reducing the number of private vehicles on the road will improve public transportation quality, making it easier to access stations and allowing the BRT system and other road-based public transit to operate more efficiently, which in turn enables fleet and route expansion.

It’s Not a Populist Policy, so Implementation is Difficult?

Jakarta does have plans. Policies to limit private vehicle usage have been in development for nearly two decades. Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) was introduced in 2006, but despite not being implemented yet, the issue of ERP continues to surface with each change in leadership. In addition to ERP, Low Emission Zones (LEZ) and Parking Management are also policies that, although partially implemented, have not yet been widely executed, resulting in little or no visible impact.

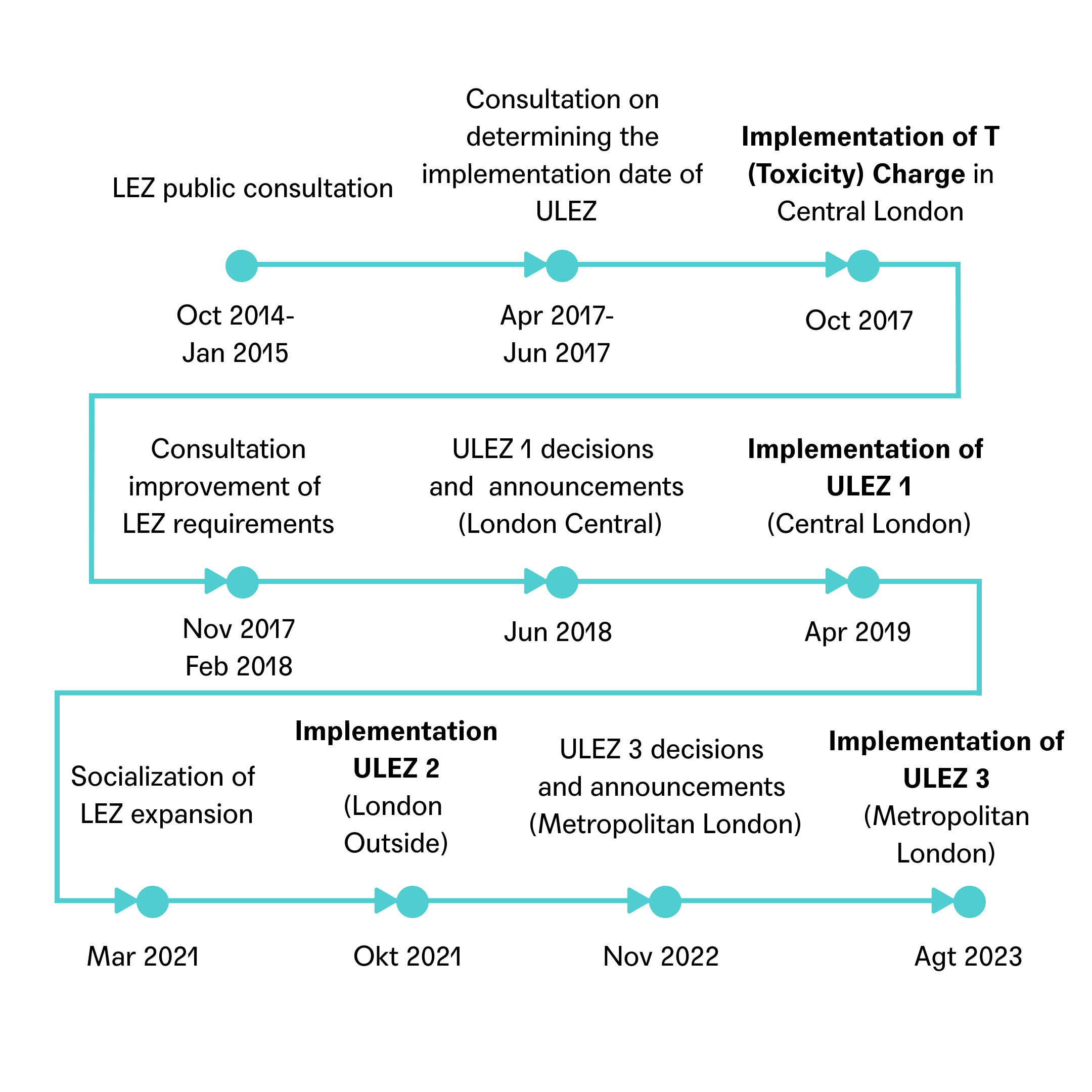

In this regard, Jakarta, as a global city, can learn from other global cities that have successfully implemented strategies to restrict private vehicle usage. For example, London has successfully implemented a Low Emission Zone (LEZ) citywide with comprehensive preparation and phased implementation. Public consultations were held from 2014 to 2017 through signage at intersections and two-way communication with community groups. Transport for London (TfL) also conducts bi-monthly evaluations to assess public perception and adjust their message as needed.

The LEZ policy began with a “Toxicity Charge” trial on October 2017 in the city center, using Euro IV emission standards. After one year of evaluation, London introduced the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) with stricter Euro VI standards in 2019. Monthly monitoring showed that ULEZ successfully increased vehicle emission compliance, leading to the zone’s expansion in subsequent years.

In addition to success stories, the failures of other cities in implementing vehicle restrictions also offer valuable lessons. For instance, Manchester failed to implement its Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) policy, even after public consultations. In 2005, the city planned to integrate transport with ERP as a primary strategy, with a socialization budget of IDR 60 billion for public discussions, customer service, school curriculums, and a website. However, through a referendum, 79% of residents rejected the policy.

Push policies like ERP, LEZ, and Parking Management often face low public acceptance. Without trials beforehand, referendums result in high rejection, especially since the public does not yet perceive the benefits of the policy. The city government was also criticized for being slow to address misinformation, with claims that ERP was merely a revenue-generating tool with no guarantee of improving sustainable transport systems.

What can Jakarta do?

From these two cities, we learn that implementing public policies requires three main stages: trials, evaluations, and expansions, with public consultations at each stage. Restriction policies, such as limiting private vehicle usage (push policies), rely on public acceptance, which can be gained through limited trials with moderate standards and conditions.

The trial phase is designed to introduce policies to the public and gather data for evaluation. The evaluation process should be conducted consistently, with clear indicators, and communicated effectively to the public. Positive outcomes, such as increased use of public transport or reduced emissions, can help build public trust in the programs. The results of the evaluation will guide the development of the program in subsequent phases.

Public consultations are key to the success of each phase of public policy. In push policies, the main goal is not necessarily high public acceptance but rather the dissemination of information and adjustments based on public feedback.

According to Pickford et al. (2024), lessons learned from restriction policies in various cities include:

- Structured Public Communication: The public must understand the policy’s goals of tackling congestion and pollution, with additional benefits like improved public transport services from ERP revenue.

- Collaboration with Stakeholders: Governments should involve experienced parties, such as academics and CSOs, as well as stakeholders, including industry and communities.

- Diversifying Communication Tools: The delivery of messages should be efficient and facilitate feedback or responses from the public.

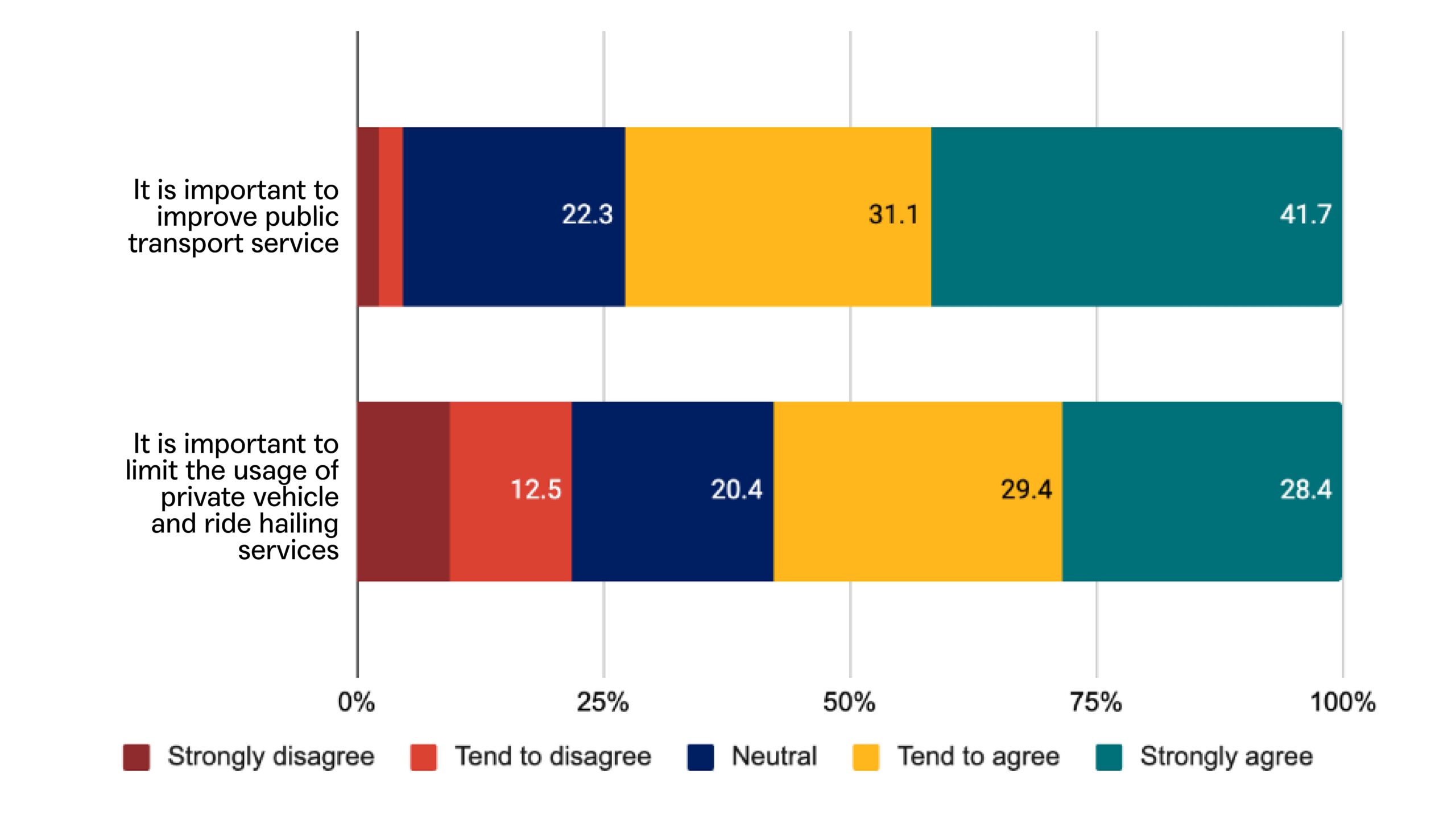

Implementing push policies in Jakarta needs to consider public perception to ensure effective consultation. ITDP Indonesia (2023) conducted a public perception survey with 1,012 respondents and analyzed responses from 511 private vehicle users. Over 75% of respondents agreed that private vehicle use contributes to pollution in Jakarta and negatively impacts public health. This indicates high public awareness of mobility issues and their negative impacts.

When asked about the types of interventions needed to address mobility issues through push and pull policies, respondents expressed a more positive view toward improving public transport services. However, 57% of private vehicle users supported policies to restrict private vehicle use, while 20% still showed confusion.

Jakarta can begin introducing more ambitious vehicle restriction policies based on existing programs like odd-even, high parking fees for vehicles that fail emission tests, pedestrianization, and Low Emission Zones (LEZ). These strategies can be scaled up to larger areas with stricter standards. For example, expanding LEZ to a larger and more targeted scale, replacing ineffective odd-even policies with ERP, and planning a more integrated parking restriction system.

In addition to implementing trial phases like other cities that have established vehicle restrictions, it is crucial to integrate these policies with public transport system development. Implementing ERP or LEZ in Jakarta’s city center should be accompanied by reliable public transport services or incentives such as cheaper public transport fares.

Implementing push policies requires determination and courage from local leaders. In Jakarta’s case, the governor plays a crucial role in ensuring successful implementation. Several gubernatorial candidates have proposed programs to increase public transport use through larger investments or cheaper service fares. However, they still believe that building flyovers/underpasses or even urban toll roads in the city will solve Jakarta’s traffic congestion.